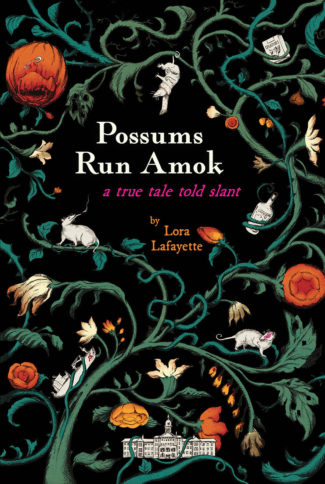

For fans of Mary Robison, mental health narratives, or the amorphous early days of punk, Lora Lafayatte’s Possums Run Amok: A True Tale Told Slant (out in June from Mercuria Press) is a gripping debut memoir about young womanhood and survival in a time in countercultural history that is ripe for revision.

Illness has many faces. So does patriarchy. In this short, punchy memoir, Lafayette offers, through the idiom of punk, a valuable revisitation of the places they intersect. Part travel-, abuse-, and sick-memoir, this coming-of-age tale takes the reader on a trip through the early-to-mid-1970s, that middle child between the hippie movement and the capital P punk explosion–this, a time when the scene was still undefined, and punk was mostly a dirty word. Through droll prose reminiscent of Robison’s Why Did I Ever (if Money Breton were on acid instead of Adderall), Possums Run Amok follows the author and her squad of teenage dirtbags as they carve out a countercultural space of their own in a Portland, Oregon that feels at once bygone and contemporary. Calling themselves “possumettes,” Lafayette and her best friend Kay later aimlessly hitch through Europe. Lafayette’s prose beautifully conveys the feeling of being young, wild, and unmedicated.

Told in brief, episodic chapters, Lafayette’s tale never strays far from the body, whether in Lafayette’s persistent hunger, her nicotine cravings, or in the tricks she turns with Kay for rent, food, and thrills. While echoing the romanticism of the protopunk era, Possums delivers an account of ubiquitous gendered violence in a way that compromises the era’s romanticism. Possums is rife with moments of nonconsensual sex, and Lafayette’s description of this violence is ever cool. For instance, in an early, grueling scene, Lafayette writes: “we were raped, as we had come to expect.” Despite the pervasive threat of violence, Lafayette remains defiant throughout the memoir, claiming: “Sex could never destroy me.” One could even personify this gendered violence as the marketable future of punk: punk as Syd Vicious, accessible to the everyday angry, young man.

A self-described Russophile and radical with a penchant for dating line-cook anarchists, Lafayette’s takes on the art, subculture and politics of the 70s are disarming and often laugh-out-loud funny. “We were freaks among freaks,” Lafayette writes. “Nothing struck us as funny as something truly ugly (especially if it wasn’t intended to be). So we played ugly music, sought out hideous works of art. Tormented ourselves, having sex with the repulsive.” As a whole, the memoir is utterly resistant to definition. That, among much else, makes it a punk classic.

During the latter part of the book, Lafayette is diagnosed with schizophrenia and then committed to a series of mental hospitals, often against her consent. Lafayette is at her most political when discussing the mental health industrial complex, calling her forced medication a “continual battle with chemical lobotomies,” and the hospital where she’s confined as “no venue in which to achieve mental health, especially to eliminate profound sorrow.” These illuminating passages, for me, echo the work of fellow-punk Sascha Altman DuBrul, former bassist of Choking Victim and founder of the now-defunct Icarus Project.

As an undergrad in the late 2000s, I joined a local branch of the Icarus Project, an organization best described as a radical mental health affinity/support group. The Icarus Project placed the concept of “mentally ill” within the context of a world that is schizophrenic. In my first meeting, silent and starry-eyed, I listened to a woman recall her year following a traumatic brain injury as one of unbridled creativity. Now on medication, that creativity was gone. I was still on antipsychotics at the time, and it felt like there was a piece of stained glass between me and reality, drenching not only my creativity, but my essence—a leech. While medicated, I couldn’t be myself in the world. It’s in these later passages that, considering Lafayette’s journey, I relish in the completion of this book as an act of protest. There is genuine power in Lafayette’s narrative, and something triumphant about it seeing the world.

Reflecting on the memoir’s subtitle, I often thought about slantness while reading Possums. Here, the slant seems less about truthiness—which, in memoirs, is never very interesting to me—and more about the narrative’s use of time. Lafayette employs what Alison Kafer calls crip time–loosely, an expansive reimagining of time that centers the experiences of disabled and neurodivergent people–throughout the memoir. In this way, Lafayette is able to bend the pages to tell the story as it feels true to herself. The two-page chapter, “A Poet,” for instance, chronicles the entirety of the relationship between Lafayette and a poet named Rick, until his eventual death. Although her illness takes up only a small portion of the book, it has an outsized presence that informs everything preceding it. This gives a certain weight, and hue, to the myriad of abuses Lafayette endures in and outside the hospital, as a woman and disabled person.

If Possums Run Amok starts ferociously, it ends brambly and morose, full of chronicles of loss, including that of the narrator’s own free will. “I lived several lifetimes in my first twenty-one years, perhaps that’s why I was deprived of more,” Lafayette remarks near the end, referring to her illness as the end of Life. Describing the onset of schizophrenia, she writes: “I was dead, my body just hadn’t realized it yet.” This statement is provocative, telling rather than asking: are illness and wellness disparate states? “So many years ago, voices held me back,” she continues, “and since I couldn’t quit them, I quit Life.” A revisionist project of Lora Lafayette’s memoir could—and will—lend itself to varied interpretations of these phrases, including, maybe, the question: Is this book, perhaps, a return to Life? Or instead, a chronicle of Living? For my own part, I don’t have an answer. I’m simply reminded of the soundtrack of my own days as a Possumette, when a little band called Defiance, Ohio screamed-sang “sometimes motion is the only thing that keeps us alive,” and we screamed-sang back, and we meant every word.

Possums Run Amok is best read at night. If you have to read it during the day, I recommend choosing a day that is overcast. I tried reading the book outside on a sunny afternoon once, but found the prose unreachable. Inside, blinds closed, the stained glass became worlds again.

Possums Run Amok: A True Tale Told Slant by Lora Lafayette, Mercuria Press, $14.95

Cory R. Calabria is a queer, multi-genre writer from Alabama. An MFA candidate at Louisiana State University, where he serves as Program Assistant for the LSU Creative Writing Program, Cory writes mostly true stories. He’s working on a collection of personal essays about casinos, counterculture, and other forms of intimacy in late-stage capitalism. Say hi at coryrcalabria@gmail.com.