Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu, despite spanning over 200 years of familial history, never drags or feels mired down in its own vastness. The first chapter, which focuses on the titular patriarch, Kintu Kidda and the origins of the curse that haunts his family, is told with the same urgency as the prologue, which depicts the brutal, senseless killing of one of his cursed descendants 254 years later. As this temporal jump suggests, Kintu is committed to an intricate multi-generational familial narrative, and begins as so many of those narratives do: with a family tree. The family tree often completes the task that a novel might fail to do—make intelligible to the reader how these disparate family members are connected. But if those simple lines connecting floating names can do the work of mapping out whose mother was related to whose father, surely the novel’s work is to tell us why those biological relationships matter; why we ought to read about those hundreds of years of sons and daughters and cousins and nieces and nephews. Kintu is not just the story of a family, but the—or a—story of Uganda, a country whose history begins before colonialization and encompasses far more than just that chapter.

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu, despite spanning over 200 years of familial history, never drags or feels mired down in its own vastness. The first chapter, which focuses on the titular patriarch, Kintu Kidda and the origins of the curse that haunts his family, is told with the same urgency as the prologue, which depicts the brutal, senseless killing of one of his cursed descendants 254 years later. As this temporal jump suggests, Kintu is committed to an intricate multi-generational familial narrative, and begins as so many of those narratives do: with a family tree. The family tree often completes the task that a novel might fail to do—make intelligible to the reader how these disparate family members are connected. But if those simple lines connecting floating names can do the work of mapping out whose mother was related to whose father, surely the novel’s work is to tell us why those biological relationships matter; why we ought to read about those hundreds of years of sons and daughters and cousins and nieces and nephews. Kintu is not just the story of a family, but the—or a—story of Uganda, a country whose history begins before colonialization and encompasses far more than just that chapter.

So much more, in fact, that despite the novel’s breadth, it noticeably omits the telling of Uganda’s colonial history. As Aaron Bady writes at The New Inquiry, “…the point is not that colonialism didn’t happen, or was inconsequential; [Makumbi’s] point is that colonialism wasn’t the only thing of consequence that did. Colonialism is a thing that happened, and can be taken for granted. But other stories are worth telling, too.” [1] Bady goes on to suggest, I think rightly, that this excising of the colonial encounter—that is, an attention to anything but the role of the Anglophone world in Uganda’s history—might be why Kintu is unavailable for purchase in the United States and Europe. It may speak volumes, too, that I only became aware of Kintu because of Bady’s essay, and that acquiring a copy of the book meant ordering directly through the publisher, Kenya-based Kwani Trust, and crossing my fingers that the international mail would come through.

Just as Uganda is more than its colonial history, though, Kintu is more than its relationship to writing (or not writing) that history. Perhaps the most fascinating thing about Kintu is how quickly the narrative makes the family tree it opens with a sort of useless tool. More than that, it exposes the inherent insufficiency of that family tree. While the major characters do appear in that genealogical representation, the narrative introduces and references many more members of this extended family throughout the novel. This overflow ultimately manifests in the final section’s family reunion. It becomes clear that the story of Kintu Kidda’s legacy is one that even at its most stripped down, in the form of simple names, exceeds the space of a single page. If that page fails to represent this family, though, the question becomes: Can the novel’s many pages represent it? This is what the novel asks too, among other things, and its answer seems to be yes, and perhaps even, yes, and this is the only way. In the final section, one of Kintu’s youngest descendants, Isaac Newton Kintu, takes in the scene of his vast family brought together in one place: “The ground has a memory he was sure: it was beyond comprehension, beyond sight and beyond touch but he knew it. Otherwise how else could he explain the hundreds of Kintu’s descendants gathered now in this place?” However, that memory that is beyond sight and tough is always incomplete. Indeed, the sudden overflow of characters in the final section speaks to the impossibility of any “complete” understanding of families or of nations. In representing this incomprehensible never-wholeness, Kintu speaks to this fundamental reality of history: the very idea of the whole story is always a fiction.

On a meta-level, “this place” where those descendants are gathered is Kintu itself. Makumbi has brought these generations together across time and geography. But this place is also Uganda, and Kintu not only locates this family story in Uganda, it takes Uganda as the subject of its storytelling as well. The temporal location of the prologue (2004) contrasts with that of the first chapter (1750) to demand that we figure out how we get from one to the other. How did the kingdom of Buganda where Kintu Kidda lived and died, lead us to Kampala, Uganda, where one of his male descendants was murdered? Makumbi does her best to draw this perpetually incomplete map in the novel’s structure. Each of the five sections that precede the final collective one tells the stories of different descendants of Kintu, but they also focus on different aspects of Uganda’s long history and its contemporary existence. The story of Kanani Kintu’s relationship with Christianity, for example, is as much a part of Uganda’s story as Isaac’s grappling with the reality of HIV/AIDS. The story Makumbi tells in Kintu is inevitably an amalgam of many stories, and they all matter.

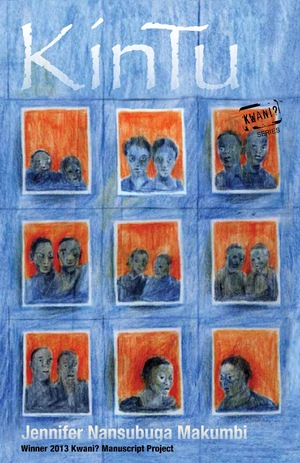

Kintu

By Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

Kwani Trust, 2014

Notes

[1] Aaron Bady, “Let’s Tell This Story,” The New Inquiry, October 8 2014, http://thenewinquiry.com/features/lets-tell-this-story/

Mary Pappalardo is a PhD student in English at Louisiana State University, where she works on 20th and 21st century American and transnational literature. She is also the Assistant Nonfiction Editor of New Delta Review, and writes semi-regularly about books at infiniteorgans.wordpress.com.