• time alive between my birth and her death: 19,186 days

• time alive between her death and this moment: 335 days

When friends ask how I’m feeling, they expect the physics of attrition. Grief, in the popular

imagination, is the particulate decrease of sadness over time. The process starts at funeral’s end,

continues until every molecule has diffused into the tissue you hold to your cheek.

Popular grief is the grief of sympathy cards. The grief of people outside grief. Grief that resolves

itself in the last fifteen minutes of the movie, sad-walks to the parking lot wondering if the book was

better.

When the bassist of his most famous trio died suddenly, at 25, in a car accident outside Geneva, NY,

Bill Evans refused to perform in public for months, played “I Loves You, Porgy” until the landlord

suggested a change of venue.

True grief conforms to no Euclidian standard. Our feelings are unstable, emotional quanta. We

grieve a past not yet happened. We regret a future once derided in others.

my mother in the coffin, laid out, surrounded by flowers. is what most disturbed me.

my mother in the coffin, laid out, surrounded by flowers. is what most comforted me.

I remember my grandmother’s couch. My mother would rest herself on it every day when she came

to pick me up after work. Sometimes she’d nap; most times she would lie there silent, eyes closed, on

cushions that would fold into a bed on nights we fled my father.

• time alive between my birth and thinking i was cursed: sometime between 2 & 4 years

When my mother died, I only dreamed about my grandmother.

Although she had been dead more than thirty years, I needed afterschool sandwiches. And tea. Hot

tea with lots of milk spilling on the plastic mat when I drank.

The old order is always asserting itself. The ghosts of Kubrick’s The Shining are among its most

aggressive citizens. The flesh covering the skeletons of the Torrance family they take as insult. Grief

grants the ability to hear their voices. Jack, the father, is the one they convince to become their

fingers.

Approaching the anniversary of my mother’s death, I wonder if the ghosts spoke to her—or if it was

the lacerations of Christ to which she answered.

a crucifix in every room / presence begging imitation, as glory

• time alive between my birth and pushing a toy car across a therapist’s carpet: 126,230,400

seconds

The “Mascot,” or “Family Clown,” is the sibling that provides entertaining interludes between abuse

incidents. The “Family Hero” is the sibling that becomes the parent everyone has been denied.

The “Lost Child” is the sibling that flees the family but leaves their body behind.

In families like mine without siblings, everyone plays multiple parts, like an Elizabethan staging of a

Shakespeare play. Most common to these situations: the father—usually the Abuser—requests the

role of “Family Clown.”

Abuse literature teaches grief applied to the family structure. The Abuser’s apology is a joke we one

day tell ourselves.

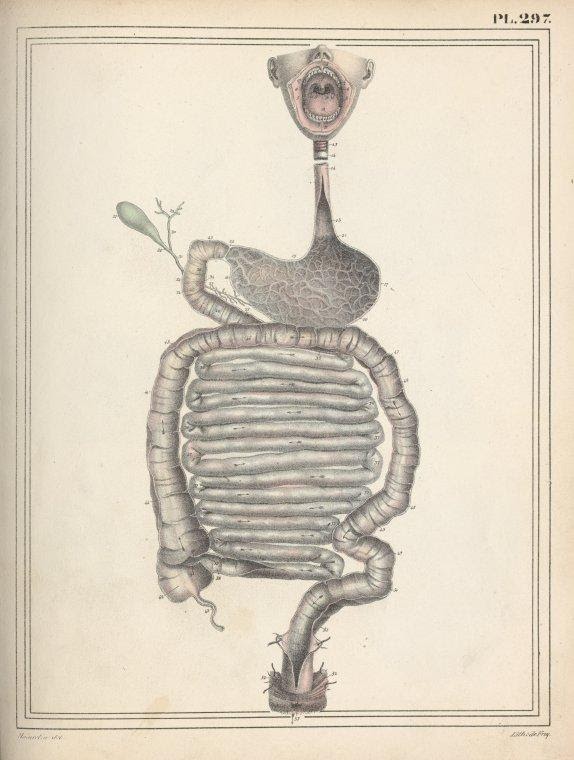

My mother spent her life awaiting a diagnosis. Every week, a different doctor. Over the course of the

decades, an entire hospital of them: Doctors of brain; of heart; of back; of bowel—of every human

part and the limbic systems that drive them.

My mother wanted these men to hand her a diagnosis she would wave like a ticket for an exotic

vacation.

In her eightieth year, when she finally learned it wouldn’t be a grand escape, but a departure by

inches on a bus leaving Port Authority during rush hour, anger took permanent residence in the

corner of her mouth, either as a sneer or bloody mash of words. Flung at me as if I were my father.

When someone asks how I’m feeling, I remember the vibration my father’s fist made on the side

of the fridge and how it returned, decades later, as the tremor in my mother’s hand.

to be hungry / to receive the curse of being fed

For my father, the only true nourishment was poison.

For my mother, in the final stages of her illness, dysphagia—or the inability to swallow foods or

liquids, resulting in coughing or throat-clearing, and feeling as if food is getting stuck.

The old woman takes another bite, forgets the partial meal already in her mouth. A minute later,

when her cheeks display a noticeable tumescence, the aide rotates in a desk chair, places two fingers

on the old woman’s wrist. The gesture seems to reconnect a wire somewhere within her. The old

woman begins tonguing brown-orange slurry into a napkin she holds to her lips. I ask if the two-

finger technique would work if I used it, but the aide shakes her head.

every time i visit, less of her to feel sorry for / less of her to be angry at

Protracted deaths are the same as unexpected ones, except we get to experience the impossibility of

resolution in slow-motion.

The story of what happened to you departed long ago. What remains is a two-panel pamphlet that

folds easily into the pocket of a hospital bathrobe. (“I was a good ________; my _______ didn’t go

hungry; didn’t want for anything.”)

Or, in the case of my mother, there was that anger. Just an inch from the lips, it was the real reason

she couldn’t swallow anything—after a life of swallowing so much.

• time alive between diagnosis and brown-orange slurry crusted across the front of her

sweater: 4,204,800 minutes

Tonight, the cemetery sequence of Easy Rider. Peter Fonda, as Captain America, cries into a stone

cheek. The goddess he has draped his body around stares outward. Fonda is tiny against her, legs

dangling over the bend of her lap. A voice off-screen recites the “Hail Mary,” the Catholic prayer for

maternal intercession. Fonda also prays. He addresses a mother with the courage to run a razor

along her neck.

The last time I see her, the nurse tells me they will be moving my mother from a “mechanical soft”

diet. Before I can learn the alternative, my mother asks where we are going for her birthday in a few

weeks.

On my way home, I get lost. A floating feeling, the sensation of being pulled by an invisible rope.

• time between my mother’s last breath and the one i just took: 364 days

At home, I can never sleep until I know whether I am going to be killed. At my grandmother’s,

behind three locks, including a dead-bolt, I am in the only place I can get any rest.

The night my father brings home a gun I am relieved. The life I had known is over: I am going to

die or my mother is finally going to leave him.

My father sits at the kitchen table, which he has moved to the middle of the room. The gun is tucked

into the shirt pocket where he usually keeps his cigarettes. As we rush past, toward the back door, he

levels its snubbed nose at the air between my mother’s head and shoulder.

When I help her over the back fence, I feel the joy of an escaping prisoner. Three months later,

when the phone calls between my father and mother start getting longer, I know I have been born

into someone else’s martyrdom.

grief is not one life, one timeline / it strolls alongside us, rearranging the petals of a daisy

Note:

Anatomy image from Science, Industry and Business Library: General Collection, The New York

Public Library. Manuel d’anatomie descriptive du corps humain, representée en planches

lithographiées.” Cloquet, Jules. Paris, Béchet, 1825. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

William Lessard’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in American Poetry Review, Best American Experimental Writing, Plume, BOOTH, Hyperallergic and the Poetry Foundation. His visual work has been featured at MoMA PS1 and is part of the special collection at Poets House.