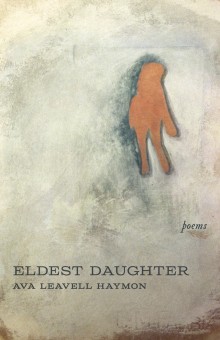

Eldest Daughter

Poems by Ava Leavell Haymon

LSU Press, 2013

Eldest Daughter by Ava Leavell Haymon is lush with fathers, ghosts, and the ghosts of our fathers. The collection’s title sets up a familial dynamic that reoccurs throughout the pieces, in iterations ranging from literal and allegorical father-daughter relationships to the “Our Father” of Christianity. The pieces are strongly grounded in narrative with an emphasis on musicality and the ancient diction of fairy tales.

Image courtesy of LSU Press

Haymon, who is the 2013-2015 poet laureate of Louisiana, sets much of Eldest Daughter in the American South. The book’s opening section in particular, “Preacher’s Daughter,” explores what it means to be raised in a Southern Baptist community. The first piece, a sestina, introduces the church of the poet’s youth along with her father and the other men of the church, focusing on the power of their speech: “the King James roll of those baritone voices,/ seminary-trained, huge without microphones.” Literal paternal figures make way for spiritual ones in the subsequent series of four poems that follow the Holy Ghost’s struggles through mundane, earthly pursuits, such as playing Little League baseball, moving to East Texas, and attending Vacation Bible School in Mississippi.

Later, the book widens geographically with a six-page prose poem that takes the form of a fairy tale. “The Castle of Either/Or” tells the story of a girl with two fathers, one “good” and one “wicked.” The poem aligns itself—through phrasing, imagery and dream logic—with the darkest of the traditional fairy tales, seething with physical and sexual violence that remains almost entirely implicit. The girl, “the first daughter,” leaves her home and embarks into the world with several items that are imbued with magical powers, yet paltry nonetheless. What she inherits from her mother, for example, is a bowl that is “too small to hold even a crumb.” When the first daughter comes to the Castle of Either/Or, she must choose which father she will remember, the good or the wicked. The choice she makes ruptures the binaries that have been set up and lends the piece an aching sense of reality.

The end of this knockout, hallucinatory tale signals a return to the real, and the remainder of the book moves progressively closer to the flesh and blood heart at its center. The penultimate piece, “Roundball” depicts, in raw clarity, the death of the poet’s father. Haymon paints a sharp picture for her reader: the basketball game that was on TV when he died, the “eggplant” color of his face after a heart attack sends him pitching forward in his chair. The specificity of this father, in the wake of allegorical and spiritual equivalents, is wrenchingly powerful.

It is easy to mistake this piece for the last of the book. However, turning the page, I found one last poem entitled “My Father Will Have Two Dozen on the Halfshell.” This relatively short piece arranged neatly on the page in five, four-lined stanzas, depicts the poet’s father in vivid life, cracking open oysters and reminiscing about past experiences as a fisherman. I could almost see him “slumped against his forearms on the metal table,” prying open shells with “that stubby knife.” I read this poem, in which the poet brings her father to life, directly after experiencing his death in “Roundball,” and closed the book with the distinct feeling of having seen a ghost.