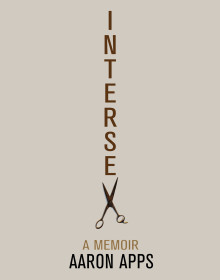

Intersex is a hybrid literary work that considers issues of gender. It’s about “I, a violence done, doing violence,” upon the “wrapped blood bubble” of the ambiguously queer body; about violence upon animal, upon self, upon world. It’s textually dynamic, a perpetual stir in form.

Intersex is a hybrid literary work that considers issues of gender. It’s about “I, a violence done, doing violence,” upon the “wrapped blood bubble” of the ambiguously queer body; about violence upon animal, upon self, upon world. It’s textually dynamic, a perpetual stir in form.

Here, Danielle Lea talks with author Aaron Apps about time, violence, bathroom narratives, transcendence, and death in Intersex:

Narrative Lines progressively accumulate throughout Intersex—building into a linear trajectory. For example, Intersex begins in Narrative Line 1, 2, 3… middles into Narrative Line 1982 (1), 1987 (1), 1988 (1), and ends in not quantification, but instead a series of Clicks—followed by a single photograph that shifts subject matter via altered camera angle and zoom.

Can you talk about the relationship between text (body), temporality (time), and the photographed image in your work? Does each function symbiotically? When language (body) dies, and title (time) falls away, what’s left?

I was attempting to describe linear temporalities as formative, as the ground or background that is constitutive of a way of being in the world, even at the site of gender. It’s not a conflation that always works, or that is always legitimate (such formal arguments rarely are), but I think it serves to illustrate how particular framed moments that move through time in expected ways—narrative movements pinned to specific temporal sites (1982, 1987, 1988)—often overlap with how gender and sex becomes normative. This is a book that’s not just about performativity and transcendence out of norms—it’s about medicine, the pharmacological, and the body’s materiality.

To turn this toward the photoshopped images at the end of the book: the images play off the text below them and are distinctly slowed down, broken, and iterative. They represent a moment where time breaks, stops, queers, and allows for reflection. There are other moments in the text that do this too: the epiphany in the bathroom scene, and the confrontation with the alligator where time is described as stopping “queerly.” These are moments that allow reflection against the expected movement of gender and time provided by medicine, capitalism, and gender norms.

Language and linear temporality, to me, even if necessary in terms of existing in our contemporary world, are very much bound up in discourses that determine who does and does not get to be included in the category of the human. Language and linear time are inextricably fraught categories as constitutive aspects of our being.

“Barbeque Catharsis” is the one of the most powerful essays I’ve read in so long. It was included as a 2014 notable essay in Best American Essays, and featured in &NOW Awards: Best Innovative Writing Anthology. It hit the stomach before the mind. I craved meat. I remember standing over a soap dispenser in a Baton Rouge laundromat, carnal and stained, a sauced face like (in your words) “we are wounds,” devouring pork ribs next to rows of washing machines. I thought of you, Aaron, and so many Intersex lines.

Retrospectively, it’s the closest I may be to understanding your gripping narrative—which isn’t close at all. It’s a narrative told unflinchingly, with a bravery I admire, a reminder of why I write. Do you want to provide a brief synopsis of your narrative?

Given where the essay goes (towards the scatological) I wonder if you were actually desiring excrement? The part of me that reads Bataille, that thinks we’re all excrement spewed out of the solar anus, thinks maybe that’s true.

Half-kidding aside, there’s something about bathrooms as sites of confusion and conflict that is pretty ubiquitous in queer literature. There is something almost cliché about bathroom narratives: there are so many of them, they sprout up like weeds in all books that approach the subject positions of people with non-normative genders. But I think they’re cliché within queer literature for a reason. Right now conservative legislators are trying to pass a law in Florida that would legalize discrimination against trans people for using bathrooms not aligned with assigned sex at birth.

I wanted to do something different with my attempt at the bathroom narrative. In many ways, it is about eating the very thing that one becomes or is made to become: animal. There’s lots of poop, bathrooms, and viscera in the story. That’s not exactly a summary, but I think it gives a hint about the essay’s contents.

“Barbeque Catharsis” begins with animals “foaming in the guts”: meat strands, hacked carcasses, butterfluid pigs, silver fat, wooden meat smoke, grey pink animal. The animal then stains lips, fingers, soils napkins, and drips on the shirt. In “Barbeque Catharsis,” the animal is consumed and becomes a part of the self. A boy sticks pins in a frog heart, squeezes plop and splooge out of a cow eye, cuts through a crunchy fetal pig ribcage, marks veins of an embalmed cat in a notebook. There’s the wonderful line: “I, a violence done, doing violence.”

You present violence as many things but also a form of sustenance, both repulsive and seemingly necessary, for not only the self but for ‘science.’ You quote Georges Bataille: “Animals are the absence of transcendence. The animal is in the world like water in water.” The conflation of the animal and human is a reoccurring motif throughout Intersex.

What, in your opinion, does our human relationship to animal say about humanity’s transcendence? Is it separate from that of the animal? What, to you, does transcendence mean? In a utopic Apps world, what would it look like?

With regards to human transcendence: recently I’ve been circling back to a short essay by Levinas about a dog named “Bobby” who approached Levinas in a concentration camp and acknowledged his face as being the same sort of face any other human might have. Levinas describes Bobby as the being the last Kantian in Germany, except he lacks the mind to universalize concepts. Bobby, like Bataille’s animals, lacks transcendence, but so does Levinas as a dehumanized body in the camps: all of Levinas’s words are, in the face of a dehumanizing murder-machine, “monkey talk.”

There’s something about occupying this flickering space, this space that puts an immovable version of the category of the human into question, that has value in the shared carno-phallo-logocentric swell of violence we all occupy. My work often tries to straddle the line between the human space that allows for the ethical spaces and categories we all occupy as given, while simultaneously asking: ait, how human are any of us anyway? Why are we using the category of the human to claim privileged positions? I’m in no way perfect in acting on, or even thinking about these things, but I am invested in a practice that moves toward more equal treatment of all bodies.

You beautifully state: “There’s a grammar to the body.” One of my favorite aspects of Intersex is its constantly flickering form. ‘Androgynous’ text is the best literary term I’ve heard in years. Intersex is so textually dynamic—in both surface and depth. What’s next? Will it still be as ruthless in its rummaging? You make me think deeply about what it means to ‘modify’ a text. Did Intersex go through any editorial modifications? I’m reminded of your Heraclitus reference: “Changing, it rests.”

At best, “hybrid” forms are an attempt to present a text in a form that speaks to it being broken of necessity: a book that speaks to its inability to occupy the space of the novel or prose manuscript, or even the sonnet or villanelle, because something else is at stake. Gender is part of it, bodily metabolism is maybe another part—but I also think class plays a large role too. My father was a janitor and farmer, and my mother has a one-year LPN degree, and something about attempting to occupy certain revered voices or forms feels very impossible to me. This might sound ridiculous coming from a doctoral student, but becoming capable as a writer and thinker is still a slow process for me. It’s a process where I attempt to remake myself in the wake of what I’ve encountered and learned. It’s quite possible that my tendency toward broken forms is a result of feeling caught in this politicized and recursive space: too much needs remaking, so how can I let it settle?

What is it about soft serve ice cream?

My mind goes directly to William S. Burroughs and thinks of some kind of apocalyptic pooping machine, and also to César Aira’s novel How I Became a Nun, which involves a gender-switching narrator and poisoned ice cream. There’s something really strange, uncontrollable yet mechanic, linear yet squishy, about soft serve ice cream. Wait, why are we talking about this?

“What we follow, what we do, becomes ‘shown’ through lines that gather on our faces” –Sarah Ahmed. Your words: “What crevice do you look back into such that you lose your life again?” Question: Is there a line (on your body, on animal body, on landscape body, on ANY body) that doesn’t “leak death”?

The thing is, I don’t want death to be posited as singular, but I want to acknowledge its existence as something structural, something we survive amid, something multiple, something that is only very minorly our own.

A vital question (for me) that I’ve encountered in graduate school and still muse over is: Who owns experience? The experiencer? Or the one who ‘writes’ experience ‘better’—thus ‘better’ able to potentially increase awareness and empathy?

Some people think experience is a free-for-all, but I’m not one of those people. I’m hesitant about co-opted narratives, about things and bodies being used without context for the false appearance of a politics, or worse, poorly outside of politics in a way that does violence to already fraught and politicized bodies. I don’t think this has to take the form of a first person account: I respect detailed investment, close research, excessive pastiche, or anything else that feels like an honest take on the thing in the background.

Turning to myself as an archive, or as the site where different aspects of the archive work their way in, allows me an access to a kind of writing I love. I can get the detail and complexity into my concerns by doing lots of research, which is something I do, but I also can swell my archive even more through the inclusion of my personal experience. Having all of this at hand opens up to a space that lets me do the kind of thinking I value, and in the end I’m invested in the thinking more than a decontextualized pile of epistemic facts.

I feel split when composing questions and probing into Intersex—an anxiety that I’m dissecting a frog heart or squeezing out eye sploog. Intersex’s Narrative Lines line into childhood. In some ways, childhood violence against animal is idyllic, so endemic–the dissecting, insects trapped in jars, sticking needles in butterfly wings, firefly bodies crushed against our own for a little light. Has your relationship to the animal, to nature, to self, altered with age?

Somewhat, but I’m still working at it. Life is practice, and we’re all here poorly in it.

Aaron Apps is the author of Dear Herculine, which was selected by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge as winner of Ahsahta’s Press’ Sawtooth Poetry Prize. Intersexwas just released with Tarpaulin Sky Press. Aaron Apps is a current PhD candidate studying poetics, sexual somatechnics, animacy and the history of intersex literature at Brown University. His poem “Queer Fat” appeared in New Delta Review issue 4.2.

Danielle Lea Buchanan pursues poetry in Baton Rouge, and fiction in New Mexico. Her work appears in McSweeney’s, Mid-American Review and other elsewheres.