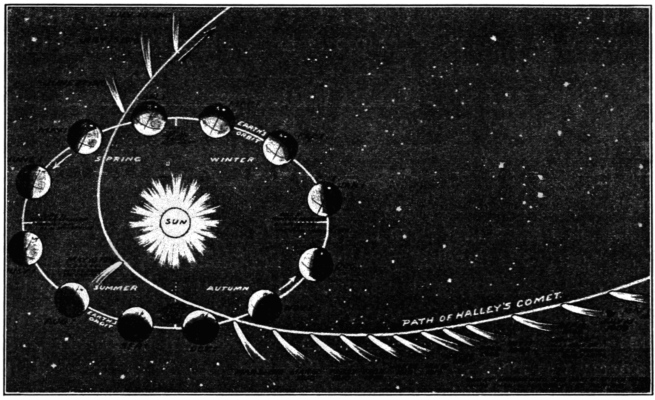

“Path of Halley Comet”*

. . .

A vast vacuum of nothing and then a bright menagerie of life. Stars and horizons. The concept of night. The universe begins its memory the moment it breaks open because space curves. This is why force. This is why time.

A bit of star breaks from a larger body and gravity polishes it a track that runs from the center of the galaxy to the end. It clicks into place and becomes compelled to follow this trajectory for a series of endless revolutions.

Meanwhile, on one of the newly formed planets, cells develop, then plants. There is sex and then there is organs and wings and tails and shells. A nautilus grows and lives and then dies, its body caught in rock and buried with time. The shell dissipates over the years until all that is left is the echo of its coiling frame.

Sex changes and then there is hair. Then people. Bodies on the ground, shifting.

Self-consciousness. Desire and disgust. The revelation that humans are uniquely equipped to assemble information. The revelation that humans are uniquely equipped to disseminate it.

Languages begin, ripen, slim down, and then dissolve. Languages bud in the most remote folds of the earth.

Somewhere someone says: creation, famine, flood.

Someone else says: disease.

In the sky, the comet endures its rounds, moves toward and then away from the sun, its center a vortex of fire and ice that boils and rages. It wants to escape, but invisible laws enforce its sentence and so it circles without end.

On earth, adults hold children’s hands—when yoked together in a crowd; while facing a threat; with necks bent back, watching the comet above.

Brothers and sisters are born. The formula for siblings is the same—semen from the same man enters the same woman. The distinction is genetic time. Same orbit, different lap.

There is war and want. There is horror and hate. There is love and longing. There are stories.

Cain and Abel. Cassandra and Helenus. Frey and Freyja. Rama and Lakshmana. Hoori and Hoderi. Mawu and Lisa. Hahgwehdiyu and Hahgwehdaetgah. Nut and Geb.

Hansel and Gretel. The story is first told by tongues now long gone. It echoes through the countryside, travels great distances and across the ages. Families install it into the brains of their children and those children grow to become adults. They then install it into the brains of their offspring. The story is mapped into the mind like a digital blueprint. The brain computes that the story is about strife, abandonment, the possibilities of leaving bits of yourself behind in order to find your way home. Home is used here figuratively, meaning that which is familiar and comfortable and safe.

Somewhere, someone says: forgive me.

Elsewhere, someone says: stop.

A spider weaves her web to catch her prey. There is a logic to the way the silk grid is roped to make her home; it follows a mathematical rule that will be known as the marvelous spiral. When she lays a sac of her eggs and that sac breaks open, hundreds of siblings are released to disperse across the world by foot or wind or larger creature. The beasts that once called the same pod home never return again.

Two middle-aged sisters. One wants children and cannot have them, so the other offers her womb. A child grows inside and is born and the sisters never tell the child in which body she was harvested.

Two young brothers. One needs a kidney and so the other goes under and his is cut out. Neither survives and their father weeps, his hands raised to the night sky.

In an abandoned field two siblings are digging. They are digging because children are interested in the art of discovery. They are digging in the ground and the sun is growing high and they are sweating. They are laughing and sweating and one sibling puts a bottle of water to her lips and it is cold and soothes her swollen throat and how she wants to finish the water in it. But she doesn’t. Instead, she hands the bottle to her brother.

Someone says: thank you.

Someone else says: never mind.

Two brothers hear the stories that orbit the countryside, decide to write them down. One of the stories is that of the siblings whose parents abandon them in the wood, and at night, over drinks, they decide this story is particularly cruel. Through the years they revise the story, carefully editing out the ugliness. Before their final edition is published, the story looks almost nothing like it once did. They do not discuss this, instead, convince themselves they’ve done right by committing it to paper. They lock hands together in understanding. Then they walk outside to witness the great traveling star move through the sky.

Meanwhile, the comet above hurls toward earth but passes it by. Its orbit curves around the sun, its brother from before the void. The comet mourns, missing its sibling. Every time it makes its return, when it approaches the sun, a bit of its cosmic flesh is dissolved, so that it is reduced.

Flowers bloom and rot, snow falls and melts, beasts cover the land, get hunted, and go extinct. Human bodies emerge from other human bodies, grow tall and walk far, shorten and slow, then lie and fail to rise.

Someone asks: How?

Someone else asks: Why?

Because the brothers wrote it down, the story of Hansel and Gretel continues to morph and evolve. It becomes an opera. It becomes a play. In some versions, there is a duck that takes them back home to join their father. In some versions, they return home only to learn that they have been transformed into adults.

A woman decides to take a new approach to rendering the story, illustrates the two siblings from above. The aerial view of the narrative strikes those who see the drawings as eerie and unnerving. When the woman disappears, someone takes her drawings to a publisher and the sketches are purchased at an inexpensive price.

A typical print run for a picture book is approved, and therefore 15,000 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel are made. They are disseminated across the world. Older bodies hold younger bodies and place before their eyes the open volume. The imagery haunts everyone in a similar vein, like a song in minor.

From above, the comet makes its pass, swings around the green and blue sphere. But as it curves to see the dark part of the planet, it is surprised to observe something new. After countless laps for an unknown set of eras, it is only now that the comet sees no part stays dark when its revolution turns it away from the sun. Instead thick deposits of light freckle the sphere’s skin. It wonders what strange forms breed there to make the dark parts flicker.

Below, ships sail across the water, and shortly thereafter, planes sail across the sky. Brothers unite with other brothers. Sisters betray each other. There is ugliness and horror and afterward, there are toasts at meals and braided hair. Hands are held in unity, heads are held in grief. There is blood on cement, and then years pass and a man points to the spot and asks what happened there, and his twin says, I don’t see anything.

In an abandoned field two siblings are digging. They are digging with small metal shovels. One sibling develops a blister and because the other knows that the best remedy is limiting friction, she lets her brother stop. They do not know that they will grow tall and wise and their roles as siblings to each other will be superseded by their roles in the world: she will be a scholar and he, a dancer. Right now they are not looking forward toward the future, but down. The brother watches his sister with admiration, and when her shovel’s thrust makes an unfamiliar sound, they look at each other as if to say, everything’s been moving toward right now.

The echo of the nautilus’s coiling frame is stamped into rock and buried for a thousand years. It is dark and protected underground, until the day the brother and sister release it from its earthen home. They do not know that one day she will study the ways stories persist when they are not written down. They do not know that one day audiences will be held breathless by the way he moves his figure. What they know is that they have found what remains of what was once a nautilus, its trace left in this rock. They pluck it from the earth and they go home, share a bowl of ice cream and take turns feeling the empty space where the creature once dwelled.

There are 12,212 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel. Some are burned in house fires. Some are drowned in baths. Some are torn apart by small hands and put into garbage bags to be put into a landfill in the earth. Inside 2,371, inscriptions are made. 957 of those inscriptions are to siblings.

After reading her the book, a brother tells his sister that the narrator of a tale lingers vestigial like an abandoned character, peripheral but present, a ghost or spirit lurking along the frame. This is how all narration is an act of speaking through another’s mouth.

Another brother tells his sister he never wants to see her again, and he doesn’t.

Someone says: Be careful.

Another: Don’t worry.

The comet approaches and this time it notices the green has been replaced with brown and grey. It wonders if the rock is sick. When the comet sees the globe get dark, it also sees the light has concentrated, gotten thicker and denser.

The nautilus shell follows the sister and brother through the years, sharing space on each of their dressers. It listens as the sister tells her brother different versions of the same tales from around the world. It watches as the brother models for his sister thirteen perfect fouette turns.

There are 7,929 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel. Some are purchased new at stores and on computers. Some are passed down and the price is haggled at sales in people’s yards. One copy, torn and tattered and with a broken spine, is handed to a middle-aged woman as her inheritance. When she opens the cover and sees the 40-year-old outline of what was once her tiny hand next to the smaller outline of her dead sister, she sobs.

Seasons turn and years pass and bodies are burned and buried. Mysteries are solved or forgotten. Problems find solutions.

Someone says: Hurry.

Someone else says: Wait.

When she goes to college, the brother tucks the nautilus shell into his sister’s bag. She finds it and months later sends it to him for his birthday, along with a catalog of other prehistoric remains. A year later, he sends it to her in the mail inside a ceramic box he’s had custom made to fits its shape. She gives it back to him before she leaves for graduate school, their initials professionally etched into the back.

A girl dies too young and her brother pounds on her headstone with his fists until his hands are bloody. He finishes school, marries, divorces, learns he cannot bear children, works a lifetime at a job at which he does not thrive. He turns 30, then 50, then 70. All this time he is haunted by the sister he lost. One day he is 80 and he returns to her grave, which he learns is covered in crawling ivy, her name illegible because the empty valleys of each letter sketched in the rock are full of soil and mold. When he arrives, the day has just broken open, the sun turning the frost on the grass to dew. He cannot read the contents of the headstone and this is how he knows that life is cruel. He turns around to sit on the patch of grass below which his sister’s form lies, leans his back against the stone that, under the grime of time, bears their shared name.

He imagines the years reversing so that the sand in the hourglass is vacuumed up rather than falls down. He is back in the moment when all of this began, their uncle reading to them from a picture book. And she is still here and smiling as if to say, there is an archive of alternate endings and every one is different than this.

There are 5,094 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel. There are 4,094 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel. There are 3,094 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel.

The comet bores its channel through the nameless elsewhere and, though it cannot see what unfolds below, there is a new sensation loitering along the borders of the orb: the fine mist of something more.

Someone says: Next time.

Someone else says: Help.

Bodies grow ill and then mend themselves, or grow ill and share that illness with others. People care for their sick and mourn them before they are gone. Siblings sacrifice for each other, unite and leave their families behind. Siblings maintain the memory of their dead by holding hands and telling stories, giving voice to the past.

Meanwhile, a brother tells a sister all his good stories, exhausts her through the evenings as he grows increasingly ill. She listens and laughs, then weeps, and they hold hands. It is then that he gives her the nautilus for the last time. And it is only then, only now that he is at the edge that she realizes she has not recorded his stories, on paper or through sound. She, the folktale scholar. It is only when he’s at the edge that she realizes her mistake, that all his stories live only in her memory now.

She says: Not yet.

The woman says: Not yet.

In the dark of the night, in a field, on her knees, a sister says: Not yet.

Someone gets the idea to create a multimodal catalog of our information. Suddenly everyone is connected. Our stories get shared more easily but also authorship gets complicated. Because space is infinite in this realm, people have to fight over something else. They decide it will be time.

Someone says: Things are getting better.

Someone else says: Things could be worse.

The story of Hansel and Gretel continues to morph and evolve. In some versions, the siblings are sent into space to fight an alien witch. In some versions, the siblings are a computer virus caught by the crumbs they leave behind. People write articles and then books about how pliable the story is and how this is the reason it has managed to persist.

A spider weaves her web to catch her prey. She lays a sac of her eggs and it breaks open so that hundreds of siblings are released to disperse across the world. This is the same way she was born and survived, found the place she now calls home. The shape of her web follows the law of the marvelous spiral, just like the starry arms of a galaxy, the twisting clouds of a hurricane, the chambers of a nautilus shell.

There are 1,485 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel. People pass stories on to be remembered. People pass stories on to forget. The world seems to get smaller and larger, at once.

In an abandoned field one sibling is digging. She thinking of how few years her brother walked this earth, how his body installed fear and beauty on the stage and possibility on the street, how that body is now reduced to bits of bone and powder. She has placed the ashes of her brother’s form into a cookie jar and now she puts the jar into the ground. She is weeping and wiping the discharge of her sorrow with her sleeve. When she has covered the cookie jar with soil, she places the nautilus on top, then curls her body around itself on earth’s crust above her brother. She does not look up at the night sky to see the comet passing.

Two space probes are released into the beyond. They move through the decades, orbiting planets and gathering data, then moving further on until they exit our universe. They are twin machines that contain a record of our world, information that can be decoded so that others might understand who we are. They pass the comet only once and each regards the other with respect.

There are 482 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel when the earth revolts. First, it is rain that lasts for months, storms so well-fueled by the water from the sky they create an ongoing core of eddying water that never tires. Then, because the earth is warm and soft from heat and rain, there are eruptions and quakes that shake and break the land, give it new dimensions. The lightning from the storms spark fires that cannot be put out. There are mudslides and erosion. There are years of heat that make the oceans bigger and the continents small. Insects that could not live through winters now reproduce in droves and with them comes disease. Everything becomes a vast and re-framed landscape, new and wild. Life becomes delicate and raw. Communities form but struggle. They seek to harness their archive of knowledge, but it lives as invisible encryptions somewhere among the stars. All analog hardware cannot access the virtual world and so it stays trapped in the ether, nearby but also remote.

Someone says: Hurry.

Someone else says: Please.

One night a young woman gets lost coming back from the river. She is her community’s water carrier and while she’s made this trip before, this time the clouds veil the stars which show her the way home. It is then she comes upon a house that is halfway intact. It looks like a rare treat in the middle of a desert, meant for only her. It takes her time to understand how to ascend the stairs, but it is her desire to see what lies at the top that compels her. When she arrives, having climbed with hands and knees, she sees a wall has been broken open and she looks upon the vista where to the north there is a grid of fires in her community’s unique pattern, and this is how she knows how to get home. When she turns around, ready to start her journey, she sees that there is a shelf where an evenly stacked collection of thin codexes lives. By some miracle, they have been spared. She pulls one from the shelf and when she opens it, she learns she cannot read the words. It looks to be one of the lost languages, which long ago died out.

She sits on the floor of what was once a child’s room and she finds—for the first time in her life—her belief becomes suspended. For while she does not understand the line of symbols, the images seem to her both haunting and familiar, like déjà vu. It is the story of two siblings, but told from above, so that when she is looking down at the page she is also looking down through the canopy of the woods. And this is how she is not viewing a pair of sutured sheets of paper but, in mind and body, has entered the forest on the page.

There are 31 copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel and no one reads the words.

A clock unmanned for a century chimes. A natural fire begins and then goes out. A nautilus fossil inscribed with two siblings’ initials sits idle in a field.

Because it makes contact with other celestial bodies and those bodies shift its balance with the sun, the comet’s orbit morphs. It grows closer to the planet known as home. One day, it fears that it may hit. As it is riding its orbit, the comet watches the earth grow ever larger until it sees what crawls on the surface which is, it learns, nothing. The planet is empty of people, just the dregs of what was once human life.

Trees grow in the center of bed frames. Moss covers bridges and bushes bust through asphalt roads. Ivy crawls up the side of skyscrapers in empty cities. Everything nests where humans once did—in the rooms of houses with collapsed roofs, in the seats of subway trains and restaurants. Mushrooms grow from open books in a variety of colors. Ferns emerge from the place where glass once sat in cars.

The discharge of mankind has been reanimated by the natural world so that the things once found important become ruins beneath a much stronger force. It cannot be known how many times the tale has been told but it is told no more, at least on this abandoned sphere. And now the comet comes to know its own finale as it races toward the polished rock it’s watched for years. As it approaches, it thinks perhaps it has been destined for this end since the moment it broke from its brother at the center of the system in which they toil. It has finally been released from its orbit, abandoned by the laws of the sky. Its approach is imminent now and it watches as its force starts to bore a fiery crater on the rock’s skin and there are four copies of The Illustrated Hansel and Gretel and then, in an instant, there are none.

Long before all this, centuries prior, two siblings are running in an abandoned field. They are running and trying to catch each other when they see a nautilus shell. The younger picks it up and flips it over, reads the initials carved into the back. He starts to dig, his sister’s body just a point on the horizon. He is hoping to find what lies below before she stops him. Her form grows larger as she approaches and he is digging with his hands, soil firmly fitting itself underneath his fingernails. Then he feels the smooth outside of a container, just as his sister draws close. He sees her head and then the way the wind blows her hair, then the wrinkles in her forehead. From the ground, he pulls out the treasure: a cookie jar. He is running on adrenaline fueled by his innate sense that magic is still possible. But his sister sees what her brother pulls from the earth and she knows. He hands it to her and she turns away from him and crouches down, lifts the lid and tips the jar to get a better look. Inside she can see that the ash is not thin, that is riddled with charred bone. She wants to believe it is a pet, but her body is too advanced to wish.

Just then a great sound cuts through the sky. The siblings look up and they know that this is it, the tailed star that was portended. This must surely be the closest it has ever been. It is breathtaking, eerie, a reminder that their bodies, like their troubles, are trivial.

Glass lasts a million years, the sister says and he holds up the nautilus fossil. She takes it, runs her fingers over the impressions. She puts it inside the jar, then tucks it snugly into the ground and covers it back up with soil. She looks at her brother when she tells him some stories should not be rewritten.

No one says: Every tale that lasts is real, even if it’s not true.

No one says: Once upon a time.

No one says anything in this region of the universe, but in the dark parts of the infinite unknown, bordering the districts of the possible, the twin machines that hold the human record approach earth’s sister world. And on the surface of that sphere, one sibling whispers to another: every end is really a beginning.

Lindsey Drager is the author of the novels The Sorrow Proper (Dzanc, 2015), winner of the 2016 John Gardner Fiction Prize; The Lost Daughter Collective (Dzanc, 2017), winner of a 2017 Shirley Jackson Award; and the forthcoming The Archive of Alternative Endings, a novel-in-stories that offers queer retellings of “Hansel and Gretel” spanning the course of a millennium in 75-year increments that correspond with Earth’s visits by Halley’s Comet (Dzanc, 2019). She is an assistant professor in the MFA program at the College of Charleston, where she serves as Nonfiction Editor of Crazyhorse.

*“Path of Halley Comet,” Popular Science Monthly, Vol. 76, January 1910. From WikiMedia Commons, public domain.