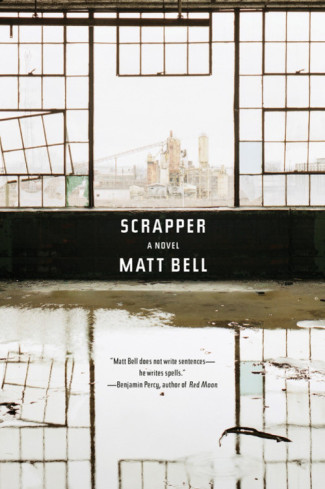

Matt Bell’s new novel Scrapper is a narrative of possibilities—of the potential energy created by our past selves, and the tension of holding two selves apart. In it a man named Kelly, fleeing from a dark past in the South to a collapsed Detroit, makes a living as a scrapper, disassembling homes for their copper innards, their raw material. Through his eyes, we are able to “See each particle a part of a whole disturbed, see the exponential increase of surface area wherever an object was broken down, the way a thing split might ignite faster than its inert whole.” Threaded throughout is a tension between what is held together and what is falling apart—or what has the potential to.

Matt Bell’s new novel Scrapper is a narrative of possibilities—of the potential energy created by our past selves, and the tension of holding two selves apart. In it a man named Kelly, fleeing from a dark past in the South to a collapsed Detroit, makes a living as a scrapper, disassembling homes for their copper innards, their raw material. Through his eyes, we are able to “See each particle a part of a whole disturbed, see the exponential increase of surface area wherever an object was broken down, the way a thing split might ignite faster than its inert whole.” Threaded throughout is a tension between what is held together and what is falling apart—or what has the potential to.

Bell’s craft shines through here, in his ability to oscillate between large-scale and personal tension. At the macro level, there’s Detroit—the Motor City full of abandoned parts, “a catalog of promise,” and at the micro level, a man teetering on the edge of personal collapse. Bell’s simple sentence structure adds tautness to these borders, creating a sense of fragility, or something barely contained. We see this tautness most clearly when Kelly finds a kidnapped boy in the basement of an abandoned home: “the moment split, and in the aftermath of that cry Kelly thought he lived both possibilities in simultaneous sequence.” Here, the protagonist becomes both the scrapper and the “salvor,” (a sort of self-termed savior), the “hero and the thief.”

Kelly’s actions, paired with Bell’s tight control of movement, explore the boundaries of this tension—how far Kelly will go as a scrapper or salvor—and what he can and cannot justify. Much of the narrative is situated within the mind of the protagonist in a series of if/then scenarios, and often end in “but then” resolutions (i.e. “If the upstairs of the blue house had been plumbed with PVC Kelly might not have gone down into the basement. But then copper in the bathroom, but then the copper price.”) The latter half of the book deals primarily with Kelly’s struggle with a sense of vigilante justice—whether to go after the suspected kidnapper, and how this action disturbingly mirrors and threatens to repeat a past Kelly has been running from.

There are three brief sections that break the main narrative apart, and create a larger context for the collapses in the novel. Though somewhat distracting, these side narratives (told in the same language of duality) offer interesting angles on versions of collapse. In the second section, situated in Florida, we see a pseudo-George Zimmerman in “The absence of doubt. The pushing back of almost.” In the third section, an abandoned Pripyat inhabited by a man who thinks, “if there was evil left in the world then it was a kind of radiation living in the earth, invisible.” These sections work to tie the main narrative into a global context, and to strengthen Bell’s thread of a connected macro/micro interaction.

There is a certain muscle and rawness in Bell’s words and their proximity to one another; it is as if form meets function in Kelly, as the narrative delves into both the structures of “The Zone”—the section of Detroit that is most collapsed—and Kelly’s mind. Words act as shovels, to haul earth away and reach towards a core. Through the dual-step narrative technique, we gradually learn that Kelly’s border between past and present selves is perhaps the shakiest of all, and the outcomes of the novel depend on his ability to keep the two from collapsing. As he struggles with these merging dualities, he realizes “the cruelty of the linear life, its adaptations; not that you would move on but that the moving on would obscure the past, bury it deep.” Yet his past is anything but buried deep, and often threatens to consume Kelly as he fights back the cyclical history of sexual abuse he fled from in the South.

Bell’s novel is like a black hole with a swirling cosmos of capability at its core. It is as if all of the actions of the characters and structures are pointing inward, and with this inward gesture, disassembling their composite parts to allow for a duality of action. And at the center of the merge, “every contact carries the potential for heat.”

Phillip Spotswood is an MFA candidate at Louisiana State University and Assistant Poetry Editor of New Delta Review. His work can be found in Heavy Feather Review, Sundog Lit, Dark Matter, and Between: An Anthology of New Gay Poetry.

The novel Scrapper (320 pages) by Matt Bell is available from Soho Press (September, 2015).