This fall, Ronlyn Domingue, author of the acclaimed novel The Mercy of Thin Air and the newly completed Keeper of Tales Trilogy, sat down at a coffee shop with NDR’s assistant fiction editor across the street from Louisiana State University, where Domingue earned her MFA in 2003. They met to discuss publishing, but wound up diving into metaphysics, the creative process, and the psychological challenge of living with the insistent characters whose stories, like it or not, Domingue is compelled to tell.

This fall, Ronlyn Domingue, author of the acclaimed novel The Mercy of Thin Air and the newly completed Keeper of Tales Trilogy, sat down at a coffee shop with NDR’s assistant fiction editor across the street from Louisiana State University, where Domingue earned her MFA in 2003. They met to discuss publishing, but wound up diving into metaphysics, the creative process, and the psychological challenge of living with the insistent characters whose stories, like it or not, Domingue is compelled to tell.

– – –

Garrett Hazelwood: So what are you doing now that you’ve finished book three of the Keeper of Tales Trilogy? What is the process of getting it published? And how far along are you?

Ronlyn Domingue: The next step is that my editor will read it; we’ll go through editing, copyediting, and proofreading. So it’ll be out late 2016, early 2017.

GH: And what will you have to do between now and then?

RD: Depending on what the comments are, it’ll probably take me anywhere from four to six weeks to edit. Copyediting will take maybe two. Proofreading maybe three days. But that’s spread out over the next few months. So between now and then, I’m doing as little as humanly possible. I’ve earned this. It’s been a very long, tough nine years. So, fortunately, I’m in the financial position to be able to do that.

GH: How did the trilogy take shape? Was it originally your idea to write three books, or was it your publisher’s decision to break it up?

RD: How can I make this a short story? The genesis of the story came in September 1990—25 years ago. There was a Women in Literature class I took, and we had an alternate assignment we could do instead of a research paper: to write a fairy tale. So I did. I wrote it about a young girl who lived in a kingdom where women weren’t allowed to read. About three years later, after I finished college, I started playing with it as a novel, but really didn’t know what I was doing. So I ended up just storing it in a closet, where it sat for a really long time.

Fast forward. Mercy of Thin Air got published in ‘05. I thought I knew what my second book was going to be, but it never really took off; so one day I was procrastinating, as we writers do, and I dug out an old computer I had from grad school, thinking maybe I had some essays I could revise to try to send to literary journals; and on that computer were all the files of the novel I had stored away. In two days, I read everything.

It’s funny, I was actually sitting right here with Jim Wilcox the day I realized what I was going to be doing, which was October 3rd, 2006; and it was like, whatever that story had been before, it went through this incredible shift that I can’t even articulate, because it somehow knew what it was going to be, even though it didn’t completely reveal itself for about nine years.

GH: How much was there at that point?

RD: Oh, maybe 25,000 words. I mean, some of the characters remain the same from the novel till now, including Aoife, who’s the narrator of The Mapmaker’s War. So there’s some of the characters and some of the same plot pieces. But it really did go through a huge metamorphosis from what it was in ‘96 to what it ended up being. I thought I was writing one big epic novel, and I thought Aoife’s narrative was going to be around 20 pages; and then very clearly, some time around 2010, I realized that was not going to happen, and that she was going to have her own book. So I thought I had a prequel and a sequel, the prequel being Aoife’s story, the sequel being Secret, the character, her story.

And once I wrote all The Chronicle of Secret Riven and turned that in to my editor, it was 239,000 words. She said, “Would you mind splitting it up into a trilogy?” I said, “Alright, I’ll do it.” I didn’t really want to, because I knew it was going to be a lot more work—and it was. So I ended up revising the first volume pretty extensively. But the second volume, the plot is the same, but it just completely blew up. So I go from 70,000 words with The Mapmaker’s War, to 127,000 published words for Chronicle, to probably about 160,000 for the last book. Which is ridiculous: the volume of words it took to get to this point.

GH: What about the transition to being a full-time writer? Were there challenges? You came straight out of your MFA and Mercy of Thin Air was your thesis, right?

RD: Yeah, so for me it wasn’t too hard because I worked full-time until I started grad school, then I worked part time during the MFA, then I was working as a grant writing consultant and teaching at the same time, so I was moving into this other experience of work that’s not typical for most people.

When I graduated with my MFA, instead of getting a full-time job, I had a friend who was doing consulting at the time, who asked me to work with her. I said okay. I can make more money doing this, working fewer hours, and still have time to write. [Laughs.] Which really was just me trying to find an agent. That’s what sucked up all my time during that period. So I worked as a consultant through the end of ‘03, through ‘04, and then once I got my advance money in ’05, I had the option to not do that anymore, so I didn’t.

GH: And what about splitting your time between the business and the creative aspects of writing?

RD: Well, searching for an agent doesn’t cost much money, especially now because so much is done online. Whereas when I was searching for an agent, email existed, but that’s not how you queried and that’s not how you sent manuscripts. So that didn’t cost much. It’s kind of hard to talk about this because everything is so different than it was, and expectations are different with social media, because now publishers expect you to basically do everything. I mean, quite frankly, they really do.

No one has ever pressured me, and I don’t know anyone who’s ever been pressured to do so, but it’s sort of encouraged, like “Go ahead, hire some outside publicists; hire some outside marketing.” And that can run you anywhere from $1,500, depending on what you’re dealing with—depending on what kind of package you are going with and what kind of firm—to $15,000-$20,000. Now, that’s out of reach for most people. You know, it’s not cheap. The really good reputable people, you’re going to be spending anywhere from $10,000 to $15,000 to market a book. You have zero, and I mean zero, guarantee that you’re going to see a return on that.

I spent a chunk of change when Mercy came out, right before the paperback, and that got me a little traction, I think. But then when the Mapmakers War came out, it was right during the whole B&N b.s. —And that was a nightmare. [In 2013, Barnes & Noble got into a dispute with Simon & Schuster, and briefly stopped selling the bulk of their S&S titles. When Ronlyn’s book came out, it wasn’t sold at Barnes & Noble.] So the money I spent there, I mean, I got a few good reviews out of it, but in terms of book sales, I can’t say it even made a difference.

So there are some writers who say, “Don’t even worry about this stuff; you just write your books and basically you are going to let the universe take care of you. If you’re going to hit, you’re going to hit, and no amount of money you can throw at something is going to change that.” And to some degree I think that is true. I mean, if it’s a book a publisher thinks is really going to have some legs, they’re going to throw a lot of money behind it and a lot of effort, but for the most part….

I mean, there are books that just take off. Look at Harry Potter. She was told that children’s books don’t sell well, and I think she got a $34,000 advance for the first book. And now? So publishers think they know who is going to hit. But there are always surprises.

GH: What about mental space? Did the business aspect ever interfere with the creative side of things?

RD: I always say the first book you write is the only pure book you will ever write, because it’s just about you and whatever you are trying to do. Unless you’re the kind of writer who’s really trying to make money, in which case you’re thinking about all the other stuff at the same time. But I wasn’t. Once Mercy came out, there was always this cloud, so to speak, of expectation over me, and I was aware of it. I was also really aware of the fact that the way my publisher thought they were positioning me was not the kind of writer I was going to wind up being.

So they were thinking Chic Lit, and “You’re going to be the next Jennifer Weiner.” But I said, “No, that is completely not what is going to happen. I don’t know what I’m going to write next, but I can guarantee that’s not where things are going.” So when I did submit my second book, and it was so different, it was shocking to everyone. But that is the book that demanded to be written.

If I could have written another book like The Mercy of Thin Air, of course I would have. In a heartbeat. It would have made my life so much easier, on so many levels. But that’s not what happened, that’s not how I operate. My novels pick me.

GH: And you didn’t just switch genres. Your writing style is completely different in the trilogy.

RD: Oh, thanks. But yeah, thematically, I think there are a lot of similarities among all of the books. But in terms of voice…

GH: Do you think that hurt your marketing? Did you lose your audience and have to win over a whole new one?

RD: Oh, absolutely. I mean there was a great deal of disappointment. Mercy is remembered fondly. There are people who really loved that book, and there was the expectation that I would play that card again; and I didn’t. You know, the only thing I can compare it to is the way Margaret Atwood has been able to, in the course of her career, pretty much span that, and not play the same note twice. I think it’s remarkable she’s been able to do that and be successful at it. That her fans, who really do read everything she writes, have been able to take that journey with her.

GH: And through that shift you were able to keep your agent and the same publisher?

RD: The agent I had for The Mercy of Thin Air left the firm around 2010. So I was sort of left to drift. But the head of the agency picked me up, so at least I had some continuity and didn’t have to find a whole new agency. But Jillian [Domingue’s agent] expected me to do exactly what I did with the first novel. So when she got The Mapmaker’s War, she was clueless what to do. She basically would have let me walk to go find another agent if I had wanted.

But I felt there was really no point, because I had a feeling that Atria [her publisher] would at least entertain the idea. I told Jillian “Just go to them—they have Right of First Refusal, anyway—and see what happens. So she did, and they picked up not just the first book, but also the second.

So, in terms of Atria, I have no idea what’s going to happen after this third book comes out, because I didn’t do what they thought I was going to do, which means, “Okay, so if she did this with the first book, and she did this with the next three, what the hell is she going to do if she writes another one?” And I have no clue what I might do. It may be nonfiction; it may be nothing. I may not write another book as long as I live. I really don’t know.

GH: What was the hardest part about the trilogy? Why did it take so much from you?

RD: [Laughs.]

GH: Because it seems like you did a lot of research for Mercy of Thin Air…

RD: I did, but that was all for content and context. I mean, I had to understand the social mores and the world of the 1920s. I needed to have accurate historical details when it was appropriate.

For the trilogy, because it happens in a time and place that is not really anchored, it only loosely mirrors our world. So Mapmaker’s is sort of like the Dark Ages. Chronicle of Secret Riven is sort of like the Victorian Age, but not really, even though I did have rules—especially for the third book. I wasn’t so concerned in the first. But in this one, if a word did not exist before 1860, it did not get used. You just have to have rules.

As far as research… [Sighs.] Man, that was just brutal. When I say it came from a really deep place, I mean that sincerely, because I was deep into some Jungian psychology, a lot of heavy material, a lot of archetypal material, research on fairy tales, folklore. I was in a headspace that was not really anchored to reality. Let’s just put it that way.

I don’t know how deep I want to get into it, but it was emotionally very hard, because the characters were coming to me in a lot of pain. So to be able to have to negotiate that, experiencing their pain in a very real way…. That was not pleasant. Hearing voices, not pleasant. I was not psychotic. I was just hearing voices. And Aoife…. Most of that book just wrote itself. The voice was just there.

GH: And do you need to withdraw from people when you’re in that mental space?

RD: Oh, completely. If I didn’t have a partner, I probably wouldn’t have my sanity now. Because it’s too difficult. Because for me it’s––and it was for Mercy, but definitely more so for the trilogy––like my body was here, but I was split. So I was always in two places at once. That’s not a way to live. And to also not have the characters––entities, people, whatever the hell you want to call them––not respecting the boundaries: where it’s, “Don’t show me that; don’t talk to me now; leave me alone,” and they don’t listen.

So it’s basically being in a constant state of, “Alright, what’s going to happen next? What new thing am I going to have to see or hear or feel?” It’s really not comfortable.

GH: You said a few times you might not write again. Is that because you feel it’s been unhealthy, psychologically?

RD: Yeah, I will not go through that again. It got scary sometimes. And I’m not the only writer who goes though that; I know. But I haven’t seen a whole lot written about it. It’s certainly something that was never discussed in any of the workshops: you could end up having what feels like psychotic episodes. So the only way I can manage this is, now, as I’m coming out of the experience, to examine how can I make meaning out of it? Why did I have to write these three books?

I don’t have the answer for that. I mean, the last one isn’t even in print yet. But how can I use what I learned about the experience, about the creative process? Because I learned a lot about the creative process, and the dark side of the creative process. What might I be able to share with those writers who may be entering into that territory completely unprepared, as I was, so that their suffering will not be lessened, but so they might have some perspective?

GH: Do you have any tips for balancing that? For living and still feeling what you need to feel to get it out on the page?

RD: Not yet. I mean, I didn’t have to go to a day-to-day job, and that was probably to my detriment, in retrospect. If I had had to leave the house every day to go to work, it probably would have created more of a buffer. But I didn’t. So I was in a 24/7 state of openness, whether I wanted to be or not. And that was really hardcore. It is very difficult to live in….

I was still able to function. I could still go to the grocery store. I don’t want it to come across that I was balled up in a fetal position and couldn’t get out of bed. Because that’s not what happened. I was able to function. But my ability to interact with people was definitely compromised, because I felt so fragile. I felt so like I couldn’t… It was so hard to contain what was happening, felt the littlest interruption might just sort of break the whole thing. So I didn’t want to risk it.

The thing I learned is, the people who love you truly love you, and they will not leave you, and the people who don’t will disappear. So I would say, have really good core people in your life. Especially if you’re going into a project that might make you really wonder about what you got yourself into.

GH: So it was hard for you, unhealthy. But was it unhealthy for the book? Or did it make it a better book to not have those anchors and to not be leaving the house?

RD: Wow, that’s a good question. I think The Mapmakers War, like I said, is the best book I will ever write, that book is incredible, and I don’t even take most of the credit for it. That one, I did need to be able to withdraw. All of them did. I think if I had had to split my time [between writing and anything else], they wouldn’t be the books they are. And that’s really hard for me to admit, actually. It’s kind of choking me up a little bit to say that. Yeah, they would not be what they are if I hadn’t been able to be in that space. What does that sacrifice mean? I don’t know. It’s sort of like a Big Art Ideas kind of a thing.

The worst was when I was really in the throes of it. I mean, things often weren’t going well, to be honest. But some days were worse than others. Some stretches of time were far worse than others. I’d find I would intentionally not go places or accept invitations because the thing I did not want to hear was, “So how’s the book going?” Because that was just enough to…

I never lost my temper with anyone, but I knew what I was going through was not something I could openly discuss. So my strategy was to not put myself in a position where anyone could even ask me that question. Because I could not even go near it. Because there was no way to answer that. I could have said, “Oh, fine.” But that would have been a lie. “It’s killing me,” would have been the truth. But most people, especially most people who don’t engage in that level of depth with creative work, can’t really understand what’s going on. It’s a bit of a mystery.

GH: Isolating?

RD: Yeah, it really is. I was fortunate to have some good friends who believed me when I’d talk about the crazy things that were going on. But I also felt really isolated because I didn’t know anybody else who was going through it. It really wasn’t until the last 8 or 9 months that I made contact with another writer who can really relate to what I go through.

Well, no, that’s not true. River and I had a good conversation, but we didn’t have the kind of relationship where we could talk all the time, so it was like every now and then I’d check in with this one particular friend who was like, “I know what you’re going through.” But she’s in Nashville; I’m here.

GH: She’s also in that space?

RD: She was for one of her books. We had a really intense conversation once about, I think it was her second novel. And I said, “That thing happened to me!” It finally felt like, yeah, someone get’s me. Someone get’s how dark it is and how thin things become when you’re in such an intense creative project. The boundaries are fluid.

GH: Do you think of it more along the lines of method acting or that you’re a medium channeling something?

RD: Definitely the channeling experience.

GH: You’re not getting into the characters; they’re getting into you.

RD: Oh yeah. The way I distinguish The Mercy of Thin Air from the trilogy is I could go in and out of The Mercy of Thin Air with my own volition, no trouble. They respected my boundaries, so I could move in, I could slip anywhere I needed to be. Whereas with the trilogy, I didn’t dare do that because I didn’t know where I was going to get lost, quite frankly. But they didn’t care. Because they just sort of co-opted my space. Sort of like, “Okay, anything I feel, you feel.” And it was really hard, it was really not pleasant…. It’s an emotional hijack. There’s no way to extricate from that. Even when you beg.

GH: So with each character there is a voice? Is there an image also?

RD: Yeah. They are who they are. For better or for worse. My character Fewmany, who is the villain in—the villain, I love calling him—oh. [Pauses, hearing a voice.] He does that…. That character has a lot of power. Fewmany is a good example of somebody who just is who he is, and there is nothing I was going to be able to do about that. I don’t think physically he’s that big, but he feels huge—he feels just giant, and powerful, and evil, and critically charming, and so smart. He loves it when I talk about him…. I’m not going to talk about him anymore. He loves that chance to kind of just be there. Such a dick.

The way I’m talking about writing—how many other writers have you heard talk about it like this? I have one very clear memory of being at this book event in 2006, and there were all these new writers I’d never met before, and it was like summer camp, like, “Oh you’re so cool; let’s hang out.” It’s so nerdy. All these introverts clustering together and sitting at the same table.

There were about six or seven of us, and somebody said, “Let’s all talk about our process.” So everybody is talking about it, and going in a circle and I’m last. After the first two I’m like, “Oh no.” After about three or four, I’m going “Oh shit.” I tell them, “Yeah, well, my characters just come to me.” I tell them about a conversation we just had, and they’re all looking at me like I’ve lost my mind, and I’m thinking “Oh man; I am really not normal.” This is hard to grapple with here.

So that’s why thinking about writing about writing from the perspective I come from is daunting for me. Because most people think, “You are a freakin’ kook.” But this is my experience. Maybe twenty percent of us are like this; I don’t know. I have no idea. But I think there is something to learn from everyone, regardless of where they fall and how they do their work.

GH: And what does it feel like now that it’s done? Do you miss your characters?

RD: No! Are you kidding? Oh God, no. They’re probably really pissed off I’m saying that. But no, I’m just relieved. I mean, it has been almost nine years of my life I’ve been in the trenches. It’s been hard.

It’s funny, I actually had an exchange on Facebook with somebody yesterday who had made a comment on what I had posted. Someone read it and wrote back, “Oh, so it’s kinda like you go on a backpacking trip with your friends and then this happens, and this happens, and this happens, but you know, you really have a lot of fun.”

I responded, “Oh no. It’s more like: imagine you go on a trip to Europe with a group of people and they are all in horrible tremendous pain, and every single day you have to listen to their stories, and now and then you stop and write them down because that’s what you promised you were going to do for them. And now do this for nine years, and now imagine you write the last sentence and they’re all at peace. That, that’s what it’s like.”

I thought for sure I was going to crash after I finished the book. That Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, I was exhausted and a mess; and then on Thursday, it was like a cloud had lifted. My friends said, “What happened to you?” “I got my life back,” I told them. I’m not trapped anymore; it’s incredible. I’m a different person from the person I was six weeks ago.

So that is what the work can do to you. If my old self could tell my younger self, “You have no idea what you’re in for,” I probably wouldn’t have believed it.

GH: That was one of my questions, actually. What would you tell a first-year MFA version of yourself?

RD: I think discipline, perseverance, and sacrifice are the three keys to getting anything written. You have to have the discipline to get your butt in the chair. And that doesn’t mean you have to do it every day, it could be three times a week, whatever that is for you, you have to sit down and do the work. The perseverance comes in where when things get hard, and they will, no matter how much you love the project, ‘cause even with Mercy things got hard. To be able to persevere though those blocks, through those tough times, to get yourself through each step until you have a draft—that’s the difference between somebody who gets published and somebody who doesn’t.

And sacrifice, I hate to say it, but it’s true: you’re going to have to give up your social media sometimes; your going to have to give up the TV, or whatever it is you do; you’re going to have to give up some of it because the work is going to demand a lot of you in terms of time. I mean, emotionally it is completely different, but just time to sit down and get the words out—that’s what it’s going to take.

On the more esoteric level, I don’t know. I’m still grappling with what happened and how to communicate what that is, especially when I know that most writers will never go that far, go that deep. They’ll touch on the edge; they’ll have experiences that are certainly weird. But I think on the spectrum, I went way, way over there.

I would say be prepared for the unexplained and the unexpected—because you really don’t know what kind of a project is going to come for you and what it will demand from you as a human being and a writer. That is, if you’re open to it.

See the NDR Blog for additional excerpts from this interview.

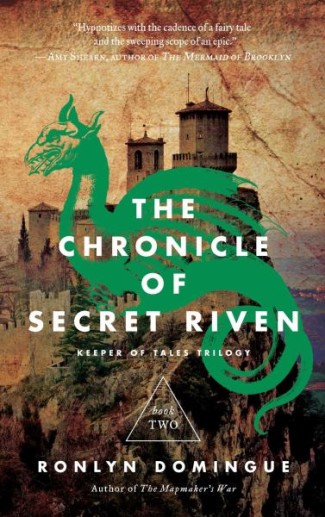

Ronlyn Domingue is the author of The Mapmaker’s War and The Chronicle of Secret Riven, Books 1 and 2 of the Keeper of Tales Trilogy. Book 3 is due to be released sometime in 2017. Her critically acclaimed debut novel, The Mercy of Thin Air, was published in ten languages. Her writing has appeared in The Beautiful Anthology (TNB Books), New England Review, Clackamas Literary Review, New Delta Review, The Independent (UK), Border Crossing, and Shambhala Sun, as well as on mindful.org, The Nervous Breakdown, and Salon. Born and raised in the Deep South, she lives there still.

Garrett Hazelwood is a first-year MFA Fiction candidate at Louisiana State University, Assistant Fiction Editor at New Delta Review, and founder/editor of The Roaming Review. His work has appeared in Eclectica and is forthcoming in The Eclectica Anthology of Speculative Fiction. He is currently at work on his first novel.