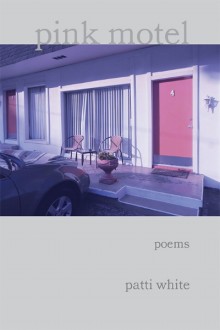

pink motel

pink motel

Patti White

Anhinga Press, 2017

Pink Motel’s central figure, Lucy, cannot contain the psychic maps of her experience but that doesn’t stop her from trying.

So dryad is a new word

for Lucy and she marks

a place where tree nymphs

find water; everything lives

in her head at once, like Keats:

Each poem in this collection seems a mapping of intersections between Lucy’s loss, grief, and revelations—an entropic system with Lucy wandering somewhere through it all. Patti White’s use of language is excess invocation—the build-up of images washing over this reader like an ink-spill on a paper map. This book spills and seeps.

Lucy comes to know her body as map in “A Circulatory System”, as “Memories / leave marks on her skin and / the skin wells up and freezes / into a map she refuses to read.” A necessary question arises, then, of whether or not the map can be rewritten. Reading across this apocalyptic quagmire of Lucy’s past, I feel as lost as the speaker, searching for some miraculous transformation or transubstantiation of all this loss. Lucy intrinsically understands in “A Venn Diagram” that, within her wasteland heart, “you can use a compass to make a circle / you can use a compass to find your way / but no path leads from one side to the other.” If Lucy cannot contain the systems of relations she exists in, then she will make her own, it seems.

As I wade through this book without section breaks, I feel as if my own bearings are crumbling, and any coagulation of meaning or sense that Lucy amasses I drink like pure water. Patti White’s poems are heat maps, labyrinths, sea charts, honeycombs, seismographs, and echolocations all designed with Lucy in mind, divining rods to aid in her quest. Her register is flat and detached, yet brimming with a fierce intelligence and searing eye for detail, which is able to track and wrangle with the wild flux of Lucy’s scope as “a string of pearls or a series of impact craters, what / she wears around her neck and collarbone” (“The Committee on Small Body Nomenclature”). If there can be a center to the maps that Lucy studies, creates, and embodies, then she realizes it is impermanence and death itself: “Who wrote this road, she asks? / how can it be so impermanent, so easily erased, as if the stones beneath the roadbed didn’t count” (“Permiograph”).

Near the end of the book, Lucy visits a print and paper lab along a river. There, amidst paper pulp and scattered type, she wishes “to emboss her forehead / with at least one true word. Let us / rest our heads on language, she says. / Let us print our way out of this sorrow” (“Letterpress”). Yet even here, within this desire, is the omnipresence and acknowledgement of loss as Lucy takes paper and ink to the river, “a poem torn from / the last printed book, and set adrift.” This collection then becomes a swollen river, Lucy and this reader simultaneously drowning in and standing on the banks of “all the drowned words we loved.” Time, here, does not seem straight nor circular but an oscillating whirlpool or black hole—Lucy and her maps spinning and spinning.

Yet the collection ends in solace, nonetheless. In “Road Mercies”, there is a “prayer for the / travelers, the living who journey on, and the preacher says / lord give them road mercies, give them road mercies, lord.” Inside Pink Motel, White blesses us with the tainted mercies of absolute clarity and unabated rapture of the world and self in their strangest topographies.

Phil Spotswood is a queer poet living in Louisiana. He is an MFA poetry candidate at Louisiana State University, and is a co-editor of Cartridge Lit. His work can be found in Hobart, Vector Press, Tagvverk, and elsewhere. He tweets @queermicrobiome