Ask, Jasmine Dreame Wagner (Slope Editions, 2015)

Ask, Jasmine Dreame Wagner (Slope Editions, 2015)

I can only say

for brevity’s sake

that every problem I have is a language.

Wagner certainly has no problem with her language in this book, but the problem of language is there throughout: what sorts of (mis)communications arise when all we seem to have in the virtual are our words, our images curated and slapped with filters, completely divorced from lived context? Note the line break in the beginning – in the inherent distance of digital communication, all we can do is say. This is not to say, however, that there is no affectivity in conversing via social media. Wagner is attuned to the charges of silences, the wait for response after the ask, how “a virtual silence is also a physical silence/if only in the intensity of our experience of it.” While the question of language and signification is at the fore of this book, this isn’t just a meditation on words. Rather, a conversation with an anonymous speaker, referred throughout as Anon, sparks memories involving technology’s role outside of the virtual “encounter”: we get students finding “the silent act/of texting a person as deeply human”, a mother complimenting an unflattering selfie. And sometimes the effects and affects of technology are implicated more obliquely: a noise show at Brooklyn’s Silent Barn brings questions of national suffering, an emphasis on smell and taste and other senses that are coded as digitally incommunicable by proxy. The digital world meets the “real” world, becomes just as real with the way light “trends” at the ends of tunnels, the way love can be desired as “a mouse clicks on a stranger in a grainy YouTube video.”

We might think of online dating and other social media as liberating in their anonymity, the commitment they don’t necessitate given this precarious late-capitalist world. But Wagner shows the obverse of this through questions of commodification, of speech and silence, of navigating affect in a world going virtual. This happens not as a diametric opposition but as a simultaneous occurrence, a messy and continuous process of becoming and belonging. Sometimes “I could tell you anything./Anonymity can do that”. Other times, and even at the same time:

Autocorrect

keeps changing ‘café’

to ‘cage.’

Justin Greene

What Fuwa Bansaku Found, Chandler Groover (sub-Q Magazine, 2016)

What Fuwa Bansaku Found, Chandler Groover (sub-Q Magazine, 2016)

In this interactive poetry piece inspired by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s woodblock prints, the reader plays as the titular samurai sent by the emperor to investigate a haunted shrine. Drawing on translated Japanese poetry, drama, and artwork, Groover presents the eerie narrative of a historical figure who discovers that the monsters which led him on this quest are anything but supernatural:

It takes but a whisper to topple a man

and a whisper in the right ear is more

deadly than a sword.

As another entry in Groover’s limited parser game series, movement through the text includes typing “A” to advance or “R” to return, and the majority of gameplay includes examining the surrounding objects using the standard command “X [object name]”. In many cases, the text guides the reader’s actions with prompts such as, “He will continue to advance” or “Fuwa Bansaku will look behind the fence”, making it accessible even for those who aren’t familiar with parser mechanics. Additionally, the choice to avoid using second person creates a distance between the samurai and the reader: you are not Fuwa Bansaku, and there are actions the reader may wish to complete to satisfy their curiosity, but as Groover reminds the reader if they attempt to examine a sacred shintai, “Fuwa Bansaku would not defile a shintai.” With these frequent prompts, Groover forces us to meditate on the questionable politics of exploring this ancient space.

Though shorter than most interactive fiction pieces, Groover’s use of verse creates a gentle rhythm, and the mechanics of parser create dramatic pause. Yet, the reader must act in order to discover what Fuwa Bansaku found behind the bamboo fence, or in the tall grass, or under a large boulder. The text fluidly moves from the objects in the shrine to Fuwa Bansaku’s memories of court, and the reader slowly discovers the genuine reason for his assignment. As a result, Groover’s engaging journey through Japanese history offers a melancholic and haunting image of the monstrous hearts of men:

Monsters inhabit history.

Some dwell within ruins.

Some dwell within men.

Some dwell within whispers

spoken about men.

Taylor Orgeron

To Breathe I’m Too Thin, Dalton Day (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2016)

To Breathe I’m Too Thin, Dalton Day (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2016)

I hand you a knife. It’s okay to cut me open, I say. I will

not be hurt. You trust me.

Dalton Day’s To Breathe I’m Too Thin bravely extends its hand at the beginning to its reader—a constantly re-scaled you—to step along with the speaker through a land of mountains, doubling moons, skies that shed feathers, and wilds wherein trees spread into woods. This in an invitation to enter not just the speaker’s world, but their inward look at the self. Neither male nor female, neither prey nor predator, the speaker is at once tied to nature and hungry to incorporate its beauty. Eschewing binaries, the desire to invite in the external muddies the chapbook like a delta, allowing multiple branches of self to converge without settling.

While the collection deftly remains off-kilter with an overwhelming sense of inability to completely internalize all that it embodies, it also reaches outward. In “Dear Wrists Turned Toward the Sun Which Shines the Loudest,” the you becomes the speaker’s own self, who then confesses:

Someone is speaking, & it isn’t

me. It’s like growing without realizing you’ve done

it. Everybody remembers when you were as big as a

bird, & all you want to say is you’ve never flown once

in your entire life.

Another outward turn—an undercurrent which runs through many of the pieces—tackles toxic masculinity. In “Un-fable” (after Rachel McKibbens), Day writes how, from the wolf, the speaker learns to be a man, to spill blood, “How to die to die to die.” Instead of becoming the wolf, the speaker runs “for so long/I learned I had to kill the wolf so I/did.”

To Breathe I’m Too Thin‘s titular poem aptly ends Day’s collection, allowing multiple threads to spill together.

In the trees we are going into the trees

with our many pairs of hands…

* * *

…It is just you and

me and you and you and you and you

walking through these woods.

At times subtle and nuanced, at others visceral and bloody, it is a walk to remember.

Raquel Thorne

When I Was A Twin, Michael Klein (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015)

When I Was A Twin, Michael Klein (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015)

I have to do something important with the pen . . .

I have to make the words fly like sparks

from the iron wheel.

Versions of self seem to preoccupy Michael Klein more than as anything else. He interrogates subjectivity and understands what’s at stake when he doesn’t. He examines the pain he holds deep inside, the joy struggling to emerge, and he makes us laugh along the way, even if occasionally we want to cry. Indeed, one of my favorite poems of this hybrid work is a brief piece of prose simply titled “Crying.” In this form of “letting go,” Klein declares, “Crying is the realest thing that can happen to you.”

Klein, though, certainly has plenty of reasons to cry. His twin brother, Kevin, with whom he was somewhat estranged, and who for decades struggled with alcoholism, died of his addiction which Michael escaped. But Klein doesn’t linger there long. Instead he keeps on exploring the self, who he is now and who he is becoming, his own gay identity, what it means to be alive, to survive. He moves between prose poems, lyrical poems, and autobiographical vignettes.

In just 63 pages we find a world of reflections on so many topics: sex, beauty, childhood, horses, horse racing, loneliness, friendship, illness, musicals and films, art, and love. Most of the pieces are autobiographical, no matter the form, as if to suggest that the self is inescapable, and that art always reflects this. And there is a latent paradox running beneath these pages: the world gives us pain and we desperately try to mitigate or deflect or simply assuage it, either with art or with substances or with whatever we think works. But do any of these “solutions” actually work? And if pain and its veil are conditions of life, are we ever truly free? Klein does arrive at a kind of answer to this riddle: his long term, very intentional sobriety. Klein has a newfound jubilance, something more than mere resignation: an ability to “love the world of what is in it and what departs it; to experience sadness without reaching for a solution to sadness; to join the sadness.” If he hasn’t found the answers to life, he has found a clue to living through turbulent times. For Klein, a union with sadness feels essential right now.

Jason Christian

Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague, Carolyn Hembree (Trio House Press, 2016)

Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague, Carolyn Hembree (Trio House Press, 2016)

Carolyn Hembree has rigged syntax onto a high-voltage battery, flipped the switch and thrown the whole thing at a Chevy on cinderblocks, caught what flames out like a pit viper. Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague is composed of five sections, each denoting the components that go into making the speaker’s time machine/Chevy hybrid—from “Safety Restraints” to “Warning Lights and Gauges” to “Customer Assistance”. The contraption seems a way for the speaker to access the cast of characters and ghosts that manifest in this book—what forms them, and what they are hiding from themselves and each other.

The speaker introduces Eyecandy and V. Cleb in “11 a.m. Aubade” as Eyecandy “leaves V. Cleb’s screen door open” and “shinnies down the mountain/past the oxeyes, the blow-up/pool, flowering satellite/dish”. This collection and the characters within are firmly, perhaps tragically, situated in place and the histories (physical, affective, spiritual) it contains. The tension between individual and its ecosystem (both literal and figurative) is taut throughout the book, and is often mapped onto the page as a violence. The fishers “who drop/one then two/dynamite bottles in/the lagoon dump” whom Eyecandy encounters on her journey down the mountain, in their violence, are mapped onto V. Cleb as he “karate kicks in his side yard. He war/cries—Kiai./BLAM/Sky high go/the baby fish”. Hembree seems to masterfully wrangle with poetic polyvalence to blur when one character’s action ends and another’s begins, in this way tying all peoples inhabiting a similar space and culture unbearably close together. The effect is a troubling implication of quantum entanglement—of a person inextricably tied to their past, its events ghosting the present. “11 a.m. Aubade” ends in the reverse movement of its beginning, as Eyecandy “climbs the mountain to his oxeyes, his blow-/up pool, flowering satellite dish”, firmly bonding the two together.

The two become further entangled with the presence of their dead child, Adeline, who haunts the book in italics—straddling the line between an imagined and corporeal body. In “V. Cleb has a Girl, Baptizes Her”, the speaker reveals “Adeline in the blow-up pool/lays her here in the side yard/half-born” and witnesses V. Cleb’s fury: “You ain’t hearing me, God. My flesh/and what else washed down/with the bath water.” Loss is felt and shared across bodies in this book. It is passed on, through generations of trauma. V. Cleb is saturated in death from the moment he is born, with his family commenting on the moment of his birth in “Necrology from His Forebears”: “This one acts like he been here before.” The death of Adeline seems the river that feeds the ecosystem of the book and the characters’ lives, and what blurs the line between what has happened, what is happening, and what will happen. The central question, for the speaker, being “Dear Paleolithicandy what if I’m surrounding/what if I’m surrounding/what if/I’m sur-/rounding/this lagoon.” And if so—how to escape it?

The book seems to answer itself in the final poem, “Why Does the Universe Go Through the Bother of Existing?” Here, the affective space of the lagoon is filled with potential:

Go and see, though, is there a basket among the reeds of this lagoon bank

Bone shard in the blown-open mine

Barn owl in the blown-open barn

Bone owl in the blown-open open

Rigged in explosives, the book bursts open time, personal history, and ecosystem to attempt a retrieval of aftermath.

Phil Spotswood

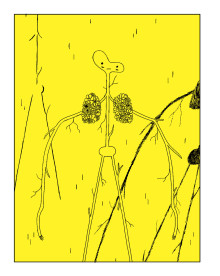

Big Kids, Michael Deforge (Drawn and Quarterly, 2016)

Michael Deforge’s work used to be described frequently as “bigfoot” cartooning, impressive for the sheer scale of the visual power of his often-grotesque stories of bodily transformation. Developing restlessly, Deforge’s work now has made an almost-complete reversal of emphasis, greatly simplifying his figure work while improving his narrative ability in great strides. It’s fitting then, that his most recent published work is also his smallest, physically. Big Kids is an octavo-sized hardback comic book. It’s an unusual design choice that works perfectly with the content of the story, smaller in scope and more intimate than Deforge’s oversized tour-de-force Ant Colony and even the children’s-book-style First Year Healthy. Big Kids is the story of a queer teenage boy who becomes a tree, or something called a tree anyway, rendered in DeForge’s sickly, spindly line.

Caption: Big Kids’ protagonist as a “tree”

The small size of the book and the dominant pink-and-yellow color scheme give extra weight to an intimate story about interior transformation. Deforge’s turn toward a more simplistic drawing style and narrative opacity make this comic feel like poetry; it’s more evocative and associational than didactic. The book turns on a divide between people who are twigs and people who are trees, which at first feels like it’s there to work as a parable similar to those of The Time Machine or Dr. Seuss’ “The Sneetches,” but as the book goes on it’s increasingly murky and multivalent as to whether tree-ness is better or even preferable to twig-ness; it seems to alienate as much as it draws fellow trees together. We don’t learn what causes treeing, only that it leads to a completely altered experience of the world. It presents a concept unusual in literature: a dichotomy with no superior position. Big Kids forces the reader to look for what’s unifying between the trees and twigs, and that information is so scarce that it’s a struggle to find any meaning in the categories. The title and the high school setting start to come together: the most socially stratified time in adolescent life unfolds into different strata that make even less sense. What’s identity? I guess it has something to do with trees. Maybe.

Tim Jones

Skull Fragments, Tim L. Williams (New Pulp Press, 2014)

Skull Fragments, Tim L. Williams (New Pulp Press, 2014)

This collection of noir short stories brings to the surface the inescapable darkness that lurks in all of us. Set in rural Kentucky where the collapse of the coal industry has left behind economic devastation, Williams’ stories focus on the heartbreaking decisions characters are forced to make in terrible but seemingly unavoidable situations, delving deep into disgusting psyches of characters you don’t want to know but can’t help but understand. Murder, rape, and substance abuse are commonplace as people simply try to live day to day. Nothing is off limits, from necrophilia to incest. These characters don’t think twice about whether the violence might be too much or too extreme; they just act. Disgust transforms into tragedy with the realization that the characters never had a chance; there was never a right choice, only a multitude of wrong ones.

East or West? I think about

California, how it always looks so clean and

hopeful in all those movies and television

shows. I tap my brake and put on my signal.

Then it occurs to me that heading west means

the sun will always be chasing me and that

every mile I travel will take me deeper into the

morning’s lie. What I need is a place where that

morning sun will soon go down. I head east

and merge into sparse traffic, moving in the

opposite direction from which the rest of the

world seems to be traveling. I settle behind the

wheel, comfortable in the fact that I’m doing

what I’ve always done – stumbling blindly into

morning in the hope that I might find darkness

as quickly as I can.

The characters in Skull Fragments have a heartbreaking awareness that moving toward the light only brings momentary relief. The darkness is inescapable, so they might as well drive toward it as quickly as possible. Though generally in the range of around thirty pages, these stories are filled with the fast-paced suspense of what these characters might do next. In a world that has shown them no mercy, mercy is not an option even in love. The moments of hope, though rare, are powerful. As Jedidiah Ayres says in his review of this collection, “Careful, some thoughts can’t be unthunk.”? These gritty stories will linger with you long after you finish reading.

Cassie Grillon

Multiple Choice, Alejandro Zambra. Translated by Megan McDowell (Penguin Random House, 2016)

In a time when authors are too often pushed to classify their work into one category or another, it is refreshing to come across a book that so unabashedly bridges fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, refusing to fit into any one box. Having grown up in the brutal military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Alejandro Zambra knows well the many mundane shapes of institutionalized oppression, and how to subvert them. His latest book is a polyvocal semi-fictional memoir written in the form of the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test, wherein every answer seems at once so right and so terribly wrong. In answering the questions posed on each page of this text, the reader is forced into a constant process of creative revision––of reordering events and excluding terms and completing or eliminating sentences. We are implicated in all the ugliness and guilt and beauty that fills these pages as we fill in the blanks:

In a time when authors are too often pushed to classify their work into one category or another, it is refreshing to come across a book that so unabashedly bridges fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, refusing to fit into any one box. Having grown up in the brutal military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Alejandro Zambra knows well the many mundane shapes of institutionalized oppression, and how to subvert them. His latest book is a polyvocal semi-fictional memoir written in the form of the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test, wherein every answer seems at once so right and so terribly wrong. In answering the questions posed on each page of this text, the reader is forced into a constant process of creative revision––of reordering events and excluding terms and completing or eliminating sentences. We are implicated in all the ugliness and guilt and beauty that fills these pages as we fill in the blanks:

51. You were a bad son, _____________ you write.

You were a bad father, _____________ you write.

You are alone, _____________ you write.

1. A) so so so

2. B) of that of that of that

3. C) but but but

4. D) because because because

5. E) and still and still and still

Most of all, though, Multiple Choice is a commentary on what and how we teach. It is a cringing and laughing tour of our ability to do wrong with the best intentions, of how instruction can become violence, and of the bitter disillusion of those whose values were shaped by an unjust system. And yet, though at least one of the voices in this slim volume “can’t fathom how during such a bitter time any sort of happiness was possible,” this test, for all the absurdity of its tragedy, remains enduringly funny. So it seems that even if we never have the answers, even if all the questions are stacked against us and the teachers have conspired to make us fail, we can always cheat an oppressive system by making the choice to look in its face, and laugh.

Garrett Hazelwood

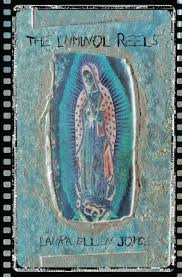

The Luminol Reels, Laura Ellen Joyce (Calamari Press, 2014)

As Laura Ellen Joyce writes, “this one’s for the sickos.” But in this world of mass eco-suicide and religious misogyny, The Luminol Reels begs the question, who isn’t a sicko? The speaker holds nothing back as she churns the soil of female existence and exhumes the generations of corpses decomposing underneath. Indeed, the book’s misleadingly petite size contains a surprising glut of rot, sadism, birth wounds and mutilation. All of these atrocities congeal into dense prose poems, coagulates which illuminate the rivers of luminol flowing through the collection’s veins. Often, the poems describe filmed scenes of murderous intensity and begin with instructions for their viewing such as, “Never insert this reel until ready for blunt trauma.” This paradigm is often twisted, however, and the viewer (or the reader) finds themselves performing in the short film vignettes:

As Laura Ellen Joyce writes, “this one’s for the sickos.” But in this world of mass eco-suicide and religious misogyny, The Luminol Reels begs the question, who isn’t a sicko? The speaker holds nothing back as she churns the soil of female existence and exhumes the generations of corpses decomposing underneath. Indeed, the book’s misleadingly petite size contains a surprising glut of rot, sadism, birth wounds and mutilation. All of these atrocities congeal into dense prose poems, coagulates which illuminate the rivers of luminol flowing through the collection’s veins. Often, the poems describe filmed scenes of murderous intensity and begin with instructions for their viewing such as, “Never insert this reel until ready for blunt trauma.” This paradigm is often twisted, however, and the viewer (or the reader) finds themselves performing in the short film vignettes:

Later, you get dreamy. You slash her open and taste

her. When she is in pieces, you hang her to cure.

When she is nothing but bone and pearl, you set

her on flat paddles in the oven.

The parcels of smoked meat are the best you’ve

ever tasted.

In other poems, the contents of the film are ignored in favor of descriptions of its surface or what strange activities the viewer enacts while reading. These mangled filmic devices allow the speaker to delve into disturbing visual imagery one moment and then spill that imagery out into the “real world” where you’re reading this review. Like the horror film The Ring, these reels will kill you, or, if you’re lucky, show you how to kill. All of this intensity of form and content creates a collection best experienced in fragments. Each poem offers enough gristle, barely hanging from the bone, to chew on its own. Read in succession, the torrents of filth can overwhelm and the clever subtleties embedded in the collection’s flesh fade to the background. Still, perhaps the speaker would argue that “Relief can be gained by visiting the mass grave.”

Ronnie Peltier

Justin Greene is a first year fiction candidate excited to be doing the poetry thing for NDR. He just graduated with a BA in English and anthropology from Wesleyan University, where he was a poet on the CT Poetry Circuit, an editor for Stethoscope Press and editor-in-chief of the campus fiction and poetry publications. When he was six, he ran off crying in the middle of performing “All Star” on the Disney Cruise but has since blossomed into the performative type.

Taylor Orgeron is an English Ph.D. student at Louisiana State University. Her areas of interest include 20th and 21st century American literature and new media. Most of her work deals with the intersections between American culture, literature, and video games. Other activities include cooking Cajun cuisine and watching any television show made by Shonda Rhimes.

Raquel Thorne is the Interviews/Reviews Editor for NDR. Additionally, she works as the managing editor of cahoodaloodaling, as an associate interviewer for Up the Staircase Quarterly, and as the president of Tandem Reader Awards. A 2016 BinderCon LA Scholarship recipient, Raquel’s poetry has been published under her legal name, Rhiannon Thorne, in Black Warrior Review, Manchester Review, The Pedestal Magazine, and The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review, among others.

Jason Christian was born and raised in Oklahoma. His work has appeared in Atticus Review, Cleaver Magazine, The Collagist, Oklahoma Review, This Land Press, and elsewhere. He lives with his dog Seymour in Baton Rouge.

Phil Spotswood serves as managing editor of NDR, and is always excited about vegetables. Raised Catholic and turned out queer, he is now a second-year MFA candidate in Poetry at LSU . His work can be found in Tagvverk, Hobart, Sundog Lit, Cartridge Lit, and Heavy Feather Review.

Tim Jones is a 3rd year Ph.D student in English with a concentration in film studies. He is from Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and enjoys pinball and Joan Didion.

Cassie Grillon grew up in Robards, KY and earned her BFA at Murray State University in Murray, KY. She is currently a first year graduate student at Louisiana State University working toward an MFA with a focus on fiction and is currently reading Nella Larson’s Quicksand.

Garrett Hazelwood is a second-year MFA candidate in Fiction at LSU and the Fiction Co-Editor here at NDR. Avid traveler, active troublemaker, and recovering footloose scallawag, he’s now settled in Baton Rouge where he’s working on his first novel and screenplay.