Keija Parssinen’s second novel tells a story of teenage girls living in a world where their very bodies are cause for suspicion and alarm. In the small town of Port Sabine, Texas, the church to which our protagonist belongs shames young women who have been “caught violating the promise of chastity” by forcing them to wear ugly, sackcloth dresses in public. Needless to say, when a dead fetus is found in a local dumpster, Port Sabine responds not with concern for the mother, but with rage and paranoia directed at all women, especially young women, of child bearing age.

Keija Parssinen’s second novel tells a story of teenage girls living in a world where their very bodies are cause for suspicion and alarm. In the small town of Port Sabine, Texas, the church to which our protagonist belongs shames young women who have been “caught violating the promise of chastity” by forcing them to wear ugly, sackcloth dresses in public. Needless to say, when a dead fetus is found in a local dumpster, Port Sabine responds not with concern for the mother, but with rage and paranoia directed at all women, especially young women, of child bearing age.

It wouldn’t be difficult to vilify this small town of witch-hunters, but Parssinen avoids taking the easy way out, opting instead for a nuanced portrait of a down-on-its-luck community attempting to find its footing in the wake of an industrial disaster that left many of its employees wounded or dead, and the local environment toxic to its residents. Through deftly shifting perspectives, Parssinen helps us understand, if not excuse, the town’s need for a scapegoat; in the face of corporate negligence, the community seems to have redirected its rage squarely at some of its most vulnerable inhabitants: young women.

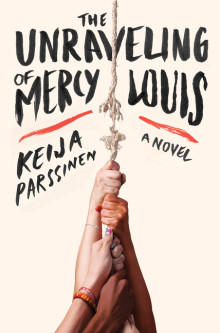

Amid all this strife however, there are a few things that draw the town together, namely the high school girls’ basketball team. The star of the team, and by extension of the town itself, is Mercy Louis. Most of the book takes places over the course of Mercy’s last summer of high school. It’s a story of first loves, female friendship and a deepened understanding of parental figures, but this is no standard coming-of-age tale. In Mercy’s case, all of these milestones are tarnished by shame, thanks to her evangelical grandmother, Evelia, who wields her faith like an iron fist. Evelia predicts that the Rapture will take place within the year, and her apocalyptic visions are just prophetic enough to warrant belief, at least in Mercy’s eyes. Because of this, Mercy’s choices and actions are imbued with a certain finality, as though all of her firsts are destined to also be her lasts.

Parssinen’s writing is lush, but rarely calls attention to itself, and when it does, it’s well worth the pause. Her descriptions of place serve to ornament and elevate what might otherwise be a rather bleak physical landscape. In describing a residential street, she writes that the homes are “modest but neatly kept, with crepe myrtle blooming decadently from every yard, the roots of ancient pecan trees coming up through the sidewalk like the tentacles of sea monsters.” Such imagery adorns the writing while underscoring thematic elements; in this case, a community that strives to keep up appearances, while the monsters of fear and blame threaten to burst up from below.

In an interview at lit blog Read Her Like an Open Book, Parssinen says that much of The Unraveling of Mercy Louis was conceived out of anger at political attacks on reproductive rights in our country. This anger, though controlled, lies coiled in the pages of the book. As a reader, though, it seems clear that the story was also born of great tenderness. Parssinen’s characters are rendered lovingly, even the most flawed of them, with enough generosity to grow our sympathies into empathy. The teenage girls at the heart of this story are sometimes cruel to each other, but they also look out for one another in ways that no one else can. As one of them says toward the end of the book, “there is grace in serving someone who can give you nothing; and that sometimes love is purest in such needs-meeting.” Parssinen weaves moments of grace and subtle revelation into every character and storyline, adding up to a whole that is ultimately as generous with light as it is with shadow.

Ana Reyes is an MFA candidate at Louisiana State University. Publications include fiction, poetry and reviews in Pear Noir, Gulf Coast, Danse Macabre, and New Delta Review. Her stories have been finalists for the Donald Barthelme Prize for short prose and the Glimmer Train Very Short Fiction Award. She recently completed her first novel.

Read Parssinen’s short story, “The Caulbearer,” in our winter issue.