Jennifer Tamayo’s playful, personal, and disturbingly sincere You Da One (2014) quickly pulls the reader into its disobedient clutches. Vacillating between moments of explosive volume and more subdued, heartfelt sentiment, You Da One introduces a speaker who wades through the language of modern technological excess on her journey to meet her father for the first time in her native Colombia. Its narrative is also made up of linguistic play that portrays an engagement with the internet and its effect on how we produce language and articulate our multiple identities—its clutter and chaos contaminating the pages just as it contaminates our daily lives. In an early section, email correspondence between the speaker and her family (replete with lingo, typos, and lax grammar) appears between repeated internet ads such as, “FIND SINCERE JEWISH SINGELS IN YOUR AREA.” These ads dominate the page, distracting from the emotionally genuine and comparatively minute email messages. Still, despite being formally overwhelmed, the emails retain their powerful resonance.

The juxtaposition of soulless clutter and internet-speak with the earnestness of familiar forms of communication sets up an absurd relationship between self and internet, which Tamayo proceeds to interrogate in several ways. For example, the speaker sometimes finds it difficult to separate her reality from her internet-saturated imagination. She asks of her father, “WHY DON’T YOU LOOK LIKE ALFRED MOLINA,” seemingly perplexed by her life’s refusal to align with the constant stream of media and images that the internet provides. Soon after, the appearance of a collage of Alfred Molina’s face and several cursors recreates the act of internet-based media consumption that fuels the speaker’s physical and linguistic journey.

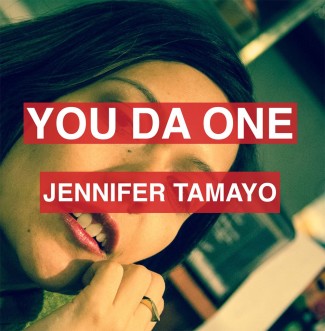

Image courtesy of Coconut Books

Alfred Molina and Rihanna (whose song “You Da One” provides the title of the book) are far from the only pop culture references presented. From Artaud to the Brazilian pop star Xuxa, the text is littered with a gamut of pop cultural and literary personas that obscure and expand the speaker’s identity. However, Tamayo is careful never to claim universality. She repeats, “There’s no WE here, there’s barely an I,” emphasizing the internet’s tendency to fragment and diminish—to hollow out a self—over its ability to foster community. Several poems explore the harmful effects of media oversaturation, especially on the bodies and minds of young women. A description of an online ad for a female mannequin, for instance, provides an understated and powerful commentary on female objectification. Ultimately, the media saturation, while playful, aggravates the dissociative and anxious aspects of the speaker’s personality. She represents this through a rumination on the multiplicity of faces: “Faces, I suppose, are a type of torture / to look like one but never be one.” This is especially intriguing given that the author’s face appears, obstructed, on the book’s cover.

A project as hyper-contemporary and formally various as You Da One presents many challenges for an author. Tamayo manages to successfully merge the book’s linguistic and narrative concerns, and this is due (among other obvious talents) to her skill in pacing. You Da One surprises with powerful images that arrest the reader’s attention only to provide context later. In this way, the book is almost novelistic in how it creates a sense of curiosity that beckons the reader forward through the chaos of pervasive internet influences. In a screenshot of an email, Tamayo writes of her book, “it’s not metaphoric. it’s a cutting.” This is an apt description that speaks not only to the interjections of internet-focused images and stylistic mischief in the body of the text, but also to the moments of emotional poignancy that manage to lacerate through the clutter. Exciting language and formal experimentation may create the most impact while reading, but the emotional residue of You Da One lingers indefinitely.

You Da One

By Jennifer Tamayo

Coconut Books, 2014

Ronnie Peltier is a poetry MFA candidate at Louisiana State University. He graduated from the University of Notre Dame with a BA in English. His work has been published in Gobbet, Deluge, and in Notre Dame’s Re:Visions journal.