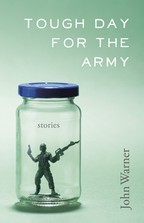

Tough Day for the Army Stories by John Warner

LSU Press September 2014

John Warner’s funny and ambitious collection of short stories, Tough Day for the Army, asks what would happen if even the most serious topics – religion, war, politics – were treated as jokes.

What if Jesus played minor league hockey and ruined another player’s career (“Second Careers”)? Can a group of gay men stalk a homophobe into realizing his ignorance (“Homosexuals Threaten the Sanctity of Norman’s Marriage”)? What happens when playground threats are taken seriously (“Notes on a Neighborhood War”)? Can an army justify war in even the most mundane places, like a hospital waiting room (“Tough Day for the Army”)?

The comedy of these stories places Warner firmly among the likes of George Saunders and Donald Barthelme, but his experiments with form make Warner’s stories so uniquely funny. This collection succeeds not just because Warner can string together a beautiful sentence (he can), but because he structures his stories to further their comedy: each story’s form builds up expectations, only for its content to subtly invert them.

The story “Return-to-Sensibility Problems after Penetrating Captive Bolt Stunning of Cattle in Commercial Beef Slaughter Plant #5867: Confidential Report” best embodies Warner’s talent for combining comedy and formal experimentation. This glorious title suggests a bureaucratic report, and it is— the story is structured as an official report of how a slaughter plant deals with cattle that just won’t die. But the true heart of the story lies in the narrator’s discovery of the horrific realities of the slaughterhouse. The reader expects that the researcher find out how to prevent all the haphazard cow killing. But the punch line is: there’s nothing anyone can do. As a slaughterhouse worker tells the researcher:

“So what I’m saying is that I’ve learned how to live with the consequences of my choices, but what this place is about is the consequences of other people’s choices, which is the messed up part.”

The worker can do his best to be careful when bolt stunning and the researcher can report on every gory detail of the process, but cows will always be sloppily slaughtered, because there’ll always be other people who want to eat cow. We try to be our best, try to be sensible about things, but there’ll always be everyone else to screw it up.

Animals in the collection seem to be the ones who are consistently in on the joke, the joke being: humans, try as they might, are a seriously self-centered bunch. The mediocre dog in “My Dog and Me”, the wry monkey in “Monkey and Man”, and the talented penguin in “Tuesday, the Bad Zoo” all offer the human characters an opportunity to confront their own narcissism, to become better, more humane versions of themselves. But ultimately the humans escape the stories without the burden of humility, and it is the animals who change—the dog never becomes, the monkey leaves for Africa, the penguin escapes the zoo— offering a wry interpretation of the collection’s epigraph: “I’m not proud, but I’m not an animal either.”

The final story of the collection, “A Love Story”, most seriously engages with the question of human ineptitude. In the story, Josh Zimmerman wrestles with what love is. He flashes between memories of his high school crush on Jennifer Mecklenberg and his current problem of proving his love to his wife Beth. The story asks questions about the nature of love (did teenage Josh really love Jennifer, or, as his Spanish teacher suggests, just want her? Is complacent love still love?), but on a deeper level, it’s a rumination on people’s capability to communicate truths to one another. How can we prove what we’re feeling is true, is real? Warner’s wonderful last lines of the story, which are the last lines of the collection, are a kind of answer:

“And so, because I am not capable of telling Beth how I love her and why I love her, I will have to show her. I will show her by writing a story. I will show her by writing these stories.”

Josh is only able to express his love for his wife by writing stories. Sometimes our deepest truths can only be expressed through fictions. Funny, isn’t it?

Warner deftly inhabits a meta-ironic voice throughout this collection with impressive formal experimentation. His stories explore what happens when people realize that no matter what they do and how well they do it, it’ll never be enough. A person is only one of billions of people. How can we rectify our individual gestures toward hope and compassion with mankind’s general narcissism, its waste? As the James Baldwin quote in the epigraph asks, what can you do when people aren’t willing to better themselves? Warner, in this collection, seems to say: why not laugh?