She watched all the videos of herself when she was small, when she was learning words and forgetting them. She does not remember this time, and that is probably for the best. It was a very painful time.

The man would tell her stories, stories about Bobo the bunny who was black and white and liked to eat lettuce and carrots. That was the whole story, and he would say, What was the bunny’s name? And she was four, and she would look at the man, and watch his face for clues, and rub at her lips and pull at her chin, and he would say, No, don’t do that. And she would remember that she was not supposed to rub at her lips or pull at her chin, and put her hand down. And he would say, What was the bunny’s name? And she would look at the man for clues, and start to raise her hand, and he would say, Nope, and she would put her hand down. And she would watch his lips. And he would say, B, b, b. And she would say, B, b, b. And he would say, What was the bunny’s name? And she would say, The bunny’s name. And he would say, B, b, b. And she would squinch up her face and squint her eyes, and put up her hand and lower her hand, and he would say, What was the bunny’s name? And he would say, Bobo. And she would say, Bobo! Very excited, and he would say, Yes! Bobo! And she would say, Bobo! And she knew that she had gotten it right. He would say, What was the bunny’s name? And she would say, The bunny’s name. He would say, B, b, b. And she would say, B, b, b. He would say, Bobo! And she would say Bobo! And he would say, Very good! And touch her hand or her head or her arm and make her feel very proud. He would say, What did the bunny eat? And she would look at him, and touch her lips, and pull at her chin, and he’d say, Nope! And she’d put her hands down. And he would say it again, and again, and what color was the bunny, again, and again, and it was so difficult and so painful, and she knew, as an adult, that her mother was sitting in another room, crying.

Her mother did not believe she’d ever get better. Luckily, she surprised her mother. So, years later, when she was fourteen and did not remember this time, the man who had taught her the words came back and said to her mother that he wanted to make a documentary about her journey, and her mother said, I never told her she used to be wordless, and he said, Think about it, then. And he left. So her mother thought. If she did not tell her daughter, what would her daughter lose? Her history, herself. She knew. So she told her daughter, and she watched the videos with her daughter, and her daughter wept and said, I always knew somehow I was different. And her mother said, But look how strong.

They had gone to great lengths to cover this past. They had moved away from their old town, from the old school. The little girl was known as someone who had never had these problems. She had a brand new life, with no associations with that past. But now, at last, she knew. She knew her whole history, and she thanked her mother, and began to speak about her history. And in the speaking, she began to see herself, and understand herself.

She goes back sometimes and looks at the old videos, though, and sees how hard she was trying then, and how difficult it was, how painful, and she gets goosebumps all up and down her arms and legs, as if her body can’t help remembering what her mind protects her from.

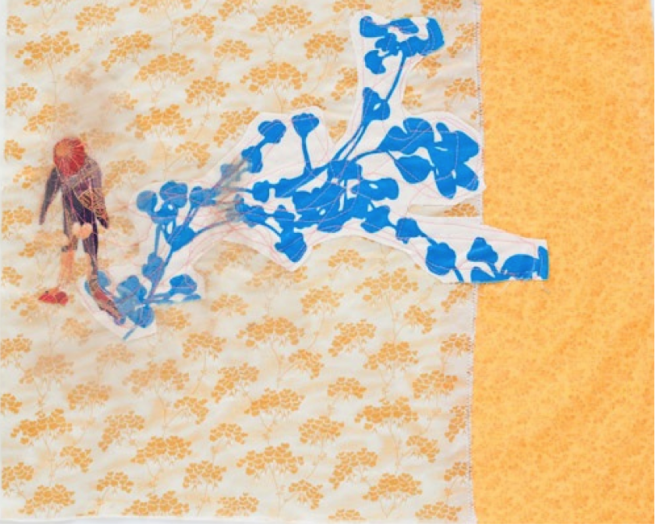

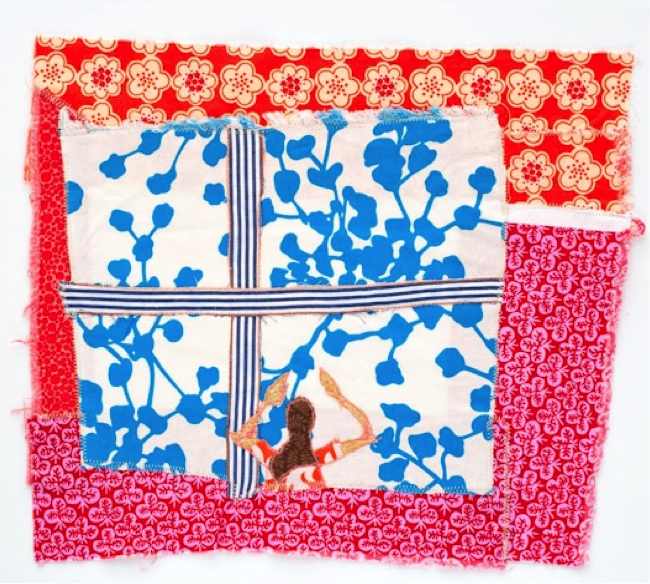

On the floor, I find first my heart—beige with gold lines through it—and then, that tiny-flowered-brown-print—my head. The other day, a bright green blade of grass, and stuck to my dog’s chin, the hand I could not find when I was putting together my body. Sometimes, I’ll find remnants of a woman’s yellow-flowered hair, a discarded gold-print leg that was the wrong shape, a too-oblong foot. Scattered all around—in the living room, or stuck to my sock, found just before bedtime.

The people who had had it done could no longer remember things—their wives’ names, their children’s birthdates, to whom the animal in the living room belonged (The dog, says the child in the orange striped shirt, is Bendo, and he is ours). They had been warned that this might happen, in the experiments, but it was a way to get out of the misery, and they were desperate, and they tried. So much of it was like it’s always been—the jaw clamped shut, the current running through the body—but now, said the people who’d done it, there was less pain, and something spiritual—visions, a gentleness in the mind. Gradients of white, the people kept repeating. Gray? the others would ask. No, it was insisted, shades of white. One woman forgot her whole family, and now she felt alone, and things were worse. A man bellowed on and on about how it hadn’t fucking worked and he couldn’t drink and he’d given up his fucking marriage, after all this. But a younger man said it was a miracle, and he was paying off his house with the antique cars he’d sold off, and he loved his children when he looked at them now. For so long, he hadn’t felt anything for them. The woman who was about to get married retrained her brain to remember things about her fiancée—where they’d met (Ontario), what he liked to eat best (fried chicken fingers with barbeque sauce, spicy), when they’d be married (two months, on a beach with humped rocks in Oregon). She felt delight. She was not alone. When it worked, it really worked, and that was worth the effort, the loss of memory, the body seething with electricity, little sparks flying from the fingertips and the earlobes and the toes, spinning into air like the body’s forgotten stars.

We made the deer of paper, covered in words, because we wanted them to know what they were. So, we wrapped them in stories, and they could read to each other at night, and understand that they were “deer,” because there was the word “deer” right there on their rump, or their neck, or their hoof. And there was snow all around them, so they were camouflaged, with the white paper and the white snow, and they were safe that way. We always wanted them to be safe, that’s why we made them. That’s why we set them in such a pretty place, so they could cherish it and it could cherish them. They were surrounded by crests and hills and acres of snow, and they could wander through it whenever they liked.

They said, though, that the one thing they really missed was having snouts and nostrils.

“We’re very grateful for our bodies,” they said, “but we wish we could smell the world, you know? We are tired of reading and not being able to smell, and taste, and understand it. We don’t understand it if we can’t take it in in every way. Do you know?”

And we said, “We understand. We can smell, yeah, we know just what you mean. Pine trees aren’t pine trees without the odor.”

But, said the best-read deer, “A rose by any other name—Doesn’t that work with smells, too? Is it the naming that makes the thing or the smell or the shape? What makes the thing the thing it is?”

And we said, “Now you have really stumped us. We weren’t ready for a discussion of philosophy. We underestimated you. We watched Bambi one too many times. It isn’t all ice-skating, is it? You really sank your teeth into this, this cognition thing.”

And the deer cocked their heads and smirked a little, and looked offended. “Uh, yeah,” said the teenaged deer, and then he muttered, under his breath, “Dumbasses,” and we heard, and ignored it, because we had done them a disservice and neglected to give them a part—nostrils, to smell. Which meant we’d short-changed them two senses: taste and smell. Which meant they could not have the whole world. And they were not really safe. They needed to smell for their food, beneath the snow. They needed to smell for the coyotes in the night, to run before they were caught.

So, we reconvened, in the big conference room with the bad lighting (we hate fluorescent lights but are sticking with them for now, to save on energy costs), and we sat around the big oval table that has no seams, and we talked about how to fashion snouts.

Edgar said, “Just poke holes into the paper,” and Jenine said, “It’s too late for that; their bodies have developed beyond just the paper. They are their own selves now. We have to mold something, from clay, and find a way to fasten it.”

“Glue,” said Bennie, and we looked at Bennie and wondered for the thousandth time how he got such long fingers and such a short body. We never asked, though, because it seemed rude.

Finally, Nadine spoke up and said, “I say we let them make their own noses. Let’s let them decided what they want, and how they want it done. Right?”

And we looked at each other and nodded, and said, “Sure, if they’re thinking theory, they can think design.”

And we got up from the table and turned off the lights and left the room. Dark. We all walked home, and wondered what we’d make for dinner. Our stomachs were growling.

The next day, we approached the deer and asked them what they thought, and they nodded their dainty deer heads and spun their ears toward us and then to each other, and then the littlest one, the teenaged one said, “Yeah, we already figured it out. Last night.”

We said, “Oh, wonderful! And?”

And they said, “We’re going to take your noses, and graft them to our bodies. It’s the only way to get the nerves and skin and everything we need to connect the nose to the brain, to make it work. What do you say?”

And our stomachs fell from our bodies to our feet, and we sat and looked at them, and realized we’d been outsmarted by the deer. And that we could not say no because we’d made them without noses, and made them suffer without noses for years, and hadn’t even considered this dilemma before, until they brought it up.

“Shit,” said Nadine. “Shit shit shit.”

And Edgar said, “Hell, no.”

And Bennie pushed his long fingers together and said, “They’re right.” And we knew they were, even though we did not want to admit it.

“How much longer can we keep our noses?” we asked, and the deer said, “Three days.”

We said, “Okay.” And now, even though we’d made them, the deer were in charge. This is always the way. Ask any robot.

We decided to make the most of our last three days with scent and taste, and we went on eating binges, and drank thousand dollar bottles of wine, and stuffed our noses into lilies and into our spouses’ hair and into their bodies. We smelled the rain and the sun and the dirt and the pizza and the steak. We smelled the eggs and the fresh apples and the baked apples and the smoke from the fires we made at night. We smelled everything, and we smelled everything so hard that, although we did not know it, the smells traveled up into our brains in little tiny particles, and rested there, in little compartments labeled “lilies,” and “pizza,” and “Jackie, my wife’s body,” and “Larry’s running socks.” We began to realize that we would miss even the bad smells, and we smelled those, too. Rotten eggs, old coffee rinds, house paint. Everything. The trash, the grass, each other’s feet.

Three days later, there we were, before the deer. And they put on their surgical masks and scrubbed into the surgery room, and we said, “Hold on, how will you cut with those hooves?”

And the oldest one looked at us and said, “Don’t worry, you won’t feel a thing, you’ll be out.” And then they put the masks over our faces, and we were out.

And when we woke up, we still had our faces and our noses and looked exactly the same, and we wondered if they’d taken pity on us, if they’d left us our sense of smell. We looked out the window from our beds, though, and saw them dancing outside, and putting their noses to the branches and the berries and the coyote poop and the nuts, and we knew that they had taken our smell, and we would be without it for the rest of our lives. We touched our bandaged noses and wondered when we’d realize that we were without it.

One of the deer came in, a white apron wrapped around her body, and she gave us packs of ice to put on our faces, even though our faces didn’t hurt at all and we still felt unchanged.

She said, “For the psychic pain,” and we took the ice packs.

Nadine said, “How long until we can take the bandages off, until we know we don’t have smell?”

And the deer said, “One day.” And she looked sorry for us, and looked out at the deer gallivanting in the snow, and walked out again, hooves clacking on the tile floor.

We saw her a few minutes later, outside, telling them all to go away. And they looked in at us, and remembered what had happened, and walked off into the snow, very quiet.

The next day, we took the bandages off, and we walked out of the hospital. We all breathed through our mouths because we were so afraid of the heartbreak that we knew would come when we realized that our smell was gone, when we really felt it. We knew how much emptier our lives would be without it, and without taste, and we tried to tell ourselves, “Well, this is how it’s supposed to be, then. This is our new life.” But it didn’t work. We were all slouched and sad. We were all so sad.

Finally, Edgar closed his mouth, out in the parking lot, and took one big breath in through his nose.

He turned to us. We waited for a shout, a cry, some sorrow, a tantrum. His eyes were wide, wide open.

“Do it,” he said. “Breathe in.”

So we all closed our mouths, and took big breaths in through our noses, and waited. And looked at each other, wondering, Could it be? And we tried it one more time. And we thought: Are we imagining? Is it just wishful thinking, that we are smelling? But, no, we were smelling! There was the smell of snow, and the smell of pine, and the smell of each other, sweating and afraid, and then delighted. We realized that everything smelled, and that there was no way to separate the thing from its smell or its color or its shape, that it needed everything to be itself, and that we needed every sense to know the world, to know ourselves, to know each other. We hugged each other and smelled each other’s happiness, which rose from our bodies like steam, like we’d just been running in the cold and our bodies were giving off heat. That’s how the smell would look.

And we thought, We are not bereft of smell or taste! We are all right! We are still whole!

And we laughed and hugged and danced around the parking lot, whooping, for so long that the deer emerged from the woods and stood at the perimeter of the lot, the farthest they could go, and watched us, wondering. Inquisitive. With their new noses, their new whole bodies, the completion of joy.

That night, exhausted from eating and smelling, we realized what must have happened, the way we stored up all the memories in our brains, the way the particles lasted, and the way the particles could combine and shift depending on what we smelled, if it was something new that was not compartmentalized already in our brains. So we had smell, all smells, and taste, all tastes. And we were not bereft or robbed of something that we needed. We realized that senses are not luxuries. And that memories are the same as senses, that we might have been tricking ourselves after all, but that it did not matter because it felt real. We had smell. We could taste. And we were delighted with ourselves and delighted with the deer and delighted with the world. And for the next week, we had a fire in the woods, with the deer, our first party with the herd, and wondered why we’d never mingled before, and we talked about Derrida and Chaucer and Woolf and Stein and Picasso, and were astounded at what they knew.

The nests are made of rope, and sit in clusters on the floor, and they are small enough for just a single bird, a small one: a chickadee. Hanging from the ceiling are pieces of metal, gouged? Shaped? They are delicate, like leaves. She says, It is about presence and absence. She says, This one is more literal than the first. The second picture is of a wax rectangle, with circles taken out of it, and on the floor are the circles, shaped into bowls. She says, People save things in bowls. There are big sheets of metal that have been melted or mixed with other metal so that their surfaces are all bubbled and burned. There are shapes on the floor that look like leaves, dusted in rust, dusted in sand, and wax mixed with sand, and it makes me want to walk into the shapes, and settle in their midst on the floor, and be very quiet.