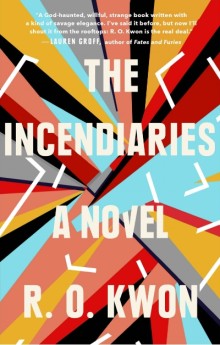

Baton Rouge was incredibly lucky to have R.O. Kwon read at this year’s Delta Mouth Literary Festival, which is run by MFA students in creative writing at LSU and features writers from across the country. Assistant Fiction Editor and Delta Mouth Fundraiser Chair Stephan Viau spoke with Kwon about residencies, food, fashion and the process behind writing her debut novel, The Incendiaries, which is forthcoming from Riverhead in July 2018.

– – –

Stephan Viau: During the panel discussions at the Delta Mouth, you mentioned how frequently you apply for residencies. From what I understand, you seem to use residencies as a way to force you to write, because you’re in a place where you’re expected to do it. Can you speak a little bit about your opinion on residencies? Were there particular residencies — or, more broadly, locations — that were really productive or inspiring, either personally or with regard to your writing?

R.O. Kwon: I love residencies. I really, really love residencies. It’s not that I require residencies to write — during the ten years I was writing my novel, I worked on it almost every day, residency or no residency. What I find particularly valuable about residencies is that you can enter into a space where you don’t have to think about anything else. You don’t have to think about what you’ll eat for dinner; you don’t have to think about your plans to see your friends that night. So, I can enter into a headspace in which, for three or four weeks at a time, I don’t have to leave my novel. That’s magical, and that’s something I can’t quite find outside of residencies.

Every residency I’ve been to has been astonishingly helpful for my writing. I am, though, particularly thankful to Yaddo. I went to Yaddo three times while I was working on my novel, and, the first two times, I went before I had a book deal. I just had a few short story publications to my name. I’m so thankful to them for that generosity, that faith. I don’t know where my novel would’ve been without them.

There’s another thing I should say about residencies. After attending a residency or two, I started understanding that there were habits I could adopt to recreate some of the residency peace and magic in my own life.

SV: In the panel discussions, you also spoke about some restrictive eating habits you have while writing. What are the benefits of controlling or limiting certain foods while you write? Are there other things you limit or have to have self-control over in order to write?

ROK: Eating is one of the greatest pleasures I know. But for lunch, while I write, I rotate two or three meals that are easy and quick to make, and nutritious. It’s not that I don’t want to eat good food while I write, it’s just that, while I’m working, I don’t want to have to make decisions about what I’m going to eat next.

For similar reasons, a couple of years ago, I tried to stop buying clothes that aren’t black. I wanted to cut down on the amount of time I spent wondering, “What am I going to wear today?” So, now, the answer’s always either a black dress or black jeans and a black shirt. Well, sometimes, I do wear grays. I think I read somewhere that Obama, while President, had multiple versions of just three suits. The analogy I’ve come across is that, each day, you have a cup’s worth of ability to make decisions. So, if I use up a lot of what’s in that cup on small, quotidian concerns, then there’s less left over for other things I want to do, like write a book.

SV: I read the really great piece you wrote for The Cut on why you don’t leave the house without putting on black eye shadow. It seems you use eye shadow works, at least partly, to consciously and intentionally dismantle certain stereotypes you’ve faced. How do you feel that your writing seeks to do some of this same work against stereotypes? Is it something you’re consciously aware of and focused on in your writing as well?

ROK: That’s a good question. I don’t know that, while writing, I consciously work against stereotypes. That said, I am very interested in making all of my characters as full and alive and human as they can be, which, in and of itself, should work against stereotypes. To put it differently—and I know a lot of writers say this kind of thing, but I think they say it because it’s true—the protagonists in my novel feel alive to me, like real human beings.

SV: Much contemporary writing, especially in fiction, seems to be in conversation with the archive. Many writers, such as Hari Kunzru, who visited and read here at Louisiana State University last fall, have spoken at length about the arduous process of inventing and rebuilding fictional worlds through archival research. What inspires your stories and characters? What research do you feel you have to do in order to create a character, like John Leal from The Incendiaries? To what extent do you see your writing as archival work?

ROK: For a short period of time, I read as much as fiction and nonfiction as I could about, for instance, cults. I did the same with terrorists, as well as the history of the fight over reproductive rights in the U.S. There’s a point when I was reading everything I could find about North Korea, but that wasn’t because my novel — it was for personal reasons. But with the cults, terrorists, and and reproductive rights, there came a point when I stopped researching. To the extent possible, I really tried to forget what I’d researched. With John Leal, I very much wanted him to be his own person. I wanted him to be a cult leader of my own creation, not directly based on anyone else. I wanted his cult to be a group that he was discovering for himself.

SV: In a brilliant interview you gave at AWP this year, you spoke about your interest in how people can know each other, but also how that knowledge is often “incomplete.” There are so many things we can never truly know about one another, and we’re often meant to be content with just getting a glimpse into the realities of those around us. Part of what made The Incendiaries so brilliant for me was the sparseness of the text and how abbreviated every chapter, and even every scene, seemed to be.. How do you think your ideas about incomplete knowledge affected how you formally structured the book?

ROK: I’m fascinated by what we can know about one another, and how incomplete that knowledge often is. There’s a substantial difference between people who believe in an all-powerful god promising eternal life, versus people who don’t. I wanted to give life to both of these worldviews. In exploring that difference, I found it felt more authentic to keep the gaps visible.

SV: To end, I think it’d be interesting to hear about what you’re reading, what work has influenced you in the past or continues to inspire you now. What are your reading practices while writing? Do you think it’s important to stay current with your reading? How might reading certain work from certain writers color your own words on the page? How might you see this outside work as a negative or a positive effect?

ROK: I’m always so interested in this question, and I always find it hard to answer, myself. There are so many books I was reading and learning from during the ten years I worked on The Incendiaries. I was reading a lot of Marilynne Robinson, for instance. I love her explorations of faith. The sheer beauty and power of her sentences has meant a lot to me. Julio Cortázar has meant a lot to me, too, and I reread his work often. I think that’s the measure: the writers I reread often are the ones I consider to be the most influential.

As for your second question: on the one hand, I don’t think it’s all that important to be current. I don’t feel as though I need to read every single book that’s out in a given year—I mean, I read between fifty and a hundred books a year, and it wouldn’t physically be possible for me to keep up with everything exciting that’s being published. On the other hand, it’s important to me to support other writers, especially more marginalized writers—writers of color, women, LGBTQ writers, everyone who gets less of a voice, less of a shot. I try to preorder their books, or to buy them in the first week they’re out.

In terms of what I read while I work, one thing I’m finding very hard, now that I’m working on my second novel, is that I still love the books I was rereading while writing my first novel. I could reread those books until I die, but I’m finding that I want to break out of my own predilections and habits. With this new novel, which I’ve been writing for two years, I keep catching myself returning to my usual tricks. I want to break out of myself, but I’m still me. Since I can’t become a different person, I’m trying to read outside of my usual preferences. I’m trying to go to photo exhibits that aren’t what I usually like. I’m trying to watch dance performances that aren’t my kind of thing. So, I’m trying to take more risks, in a way. We’ll see how that goes!

As for others’ work coloring my own writing, I don’t think of that as being a problem. I wrote The Incendiaries over ten years. I wrote and rewrote every sentence of that book I don’t know how many times. I read so many books over that time, you know? I hope anything that stayed around did so because it felt true to the book, true to the story. I suppose that’s one benefit of working on a book for so long!

R.O. Kwon’s first novel, The Incendiaries, is forthcoming from Riverhead in July of 2018. She is a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, Vice, BuzzFeed, Noon, Time, Electric Literature, Playboy, San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere. She has received awards and fellowships from Yaddo, MacDowell, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Omi International, and the Norman Mailer Writers’ Colony. Born in South Korea, she’s mostly lived in the United States.

Stephan Viau is from Montréal, Canada. He currently lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he is an MFA poetry candidate at Louisiana State University. Apart from happily being a member of the Delta Mouth Literary Festival team, Stephan has worked as an assistant fiction editor for New Delta Review, a chief designer and editor of The Busan Writers’ Anthology, and as an associate editor of Sans Merci.